Segregating gilts and sows into sub-populations based on parity and providing different nutritional regimes can increase the number of pigs born per litter and per sow lifetime, says Dr. Dean Boyd, of the Hanor Company, Franklin, Kentucky. This is because the amount and type of nutrients required by young, immature sows (1-2 litters and older females (>5 litters) is very different, he told delegates at the Manitoba Swine Seminar. Furthermore, such an approach compliments health and reproductive considerations, he says.

The fist litter female is especially vulnerable to body protein loss during lactation, explains Boyd. “The foremost consideration is to formulate and feed to conserve body protein loss, since there is a direct effect of this on wean to estrus (WEI) interval and second litter size,” he says. “For example, a 4kg body protein loss during first lactation is sufficient to reduce second litter size by 0.75 pigs, whereas, in contrast, limiting protein loss to less than 2 kg can result in a second litter size 1.0 higher than the first.” WEI increases in proportion to body protein loss and it is not uncommon for it to be extended by up to 10 days for gilts that have raised a large litter, milked well and suffered too much protein loss. “Unfortunately, this is sometimes interpreted as ‘reproductive failure’ and may result in early culling from the herd,” notes Boyd.

Total pigs born and born alive increase until the third litter, are then constant until about litter 5 or 6 and, thereafter, a progressive decline is observed. Boyd says this parity-related decline seems premature from a reproductive perspective. “The lost opportunity is probably in the order of 1.8 to 3.3 pigs per sow lifetime, depending on whether productive life is 8 or 10 litters,” he believes. “We hypothesize that this is due in part to the progressive decline in micro-nutrient profile as the sow ages.”

Micro-nutrient deficiency in older sows

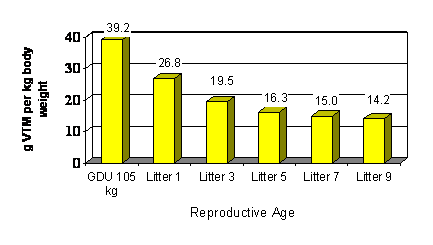

Micro-nutrients consist of Vitamins and Trace Minerals (VTM) and represent 0.12-0.15% of the diet but about 50% of the nutrients. In theory, micro-nutrients are formulated in diets at levels that prevent deficiency and include a margin of safety. However, says Boyd, there is a steady decline in the “safety margin” with increasing reproductive age. The reduction in body mineral levels that has been observed is most likely because pregnancy feed intake is held about constant (once body condition has been restored) across all parities, in order to limit growth. However, body weight progressively increases with reproductive age, Boyd points out. “This ‘constant’ feed policy is appropriate for protein and energy needs, however, it probably does not work for VTM because the amount that is required to support normal tissue metabolism increases with the increase in tissue mass,” he says. This results in a marked decline in the grams of VTM/kg body weight with increasing parity (Figure 1). “The problem is that this occurs with each pregnancy and, to a lesser extent, in lactation,” Boyd explains. “Thus, the older, heavier sow is placed at increasing nutritional risk, reproductively and immunologically.”

Figure 1: Example calculation of declining Vitamin – Trace mineral intake

with advancing reproductive age, g VTM / kg body weight

(Calculated by Boyd and Hedges, 2004, using PIC USA 2002 ADFI x

sow weight by parity, assuming 0.149% dietary VTM )

The hypothesis that an age-related decline in litter size might be nutrition related was tested in the mature sow (parities 3-10) sections of two Hanor farms. In each farm, parity segregation is practiced by designating one section for sows of parity 3 or more. In the trial, control sows received 0.15% VTM as usual, whereas the test diets for older sows were designed to provide the same VTM per kg bodyweight for a P-7 female as would be provided to a P-3 sow. The annual cost of this increase was approximately $1.69 per sow, compared to the control diets. Evaluation of herd data showed that the diets equalized for VTM did, in fact, improve performance. “Litter size weaned was improved for sows in parities 4 to 10 by an average of 0.6 pigs per litter of 1.44 pigs/sow/year,” notes Boyd. “However, sow viability was not significantly improved during the term of this study”.

The concept of organizing the sow farm in order to nutritionally manage younger and older females differently, was originally demonstrated in the Hanor system by dividing the herd into three sub-populations, however, this has now been reduced to two. This nutrition-specific approach has been shown to lead to increased lifetime pig output and reduced risk to sow viability with no increase in feed cost per weaned pig. “For young females, the expected outcome is to improve lifetime pig output by producing a large first litter and then to manage her in a way that does not compromise second litter size,” say Boyd. “Once P-1 females are successfully re-bred and managed to 30 days of gestation, then the need for specialized ‘young sow’ nutrition probably ends.” However, he notes, there may be health-based reasons for also keeping younger sows in this sub-population.