A note on genetic parameters of gilt responses to humans

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on July 25, 2011 | No Comments

In livestock production pigs are handled frequently by humans from their first day of life. Negative experiences with humans result in chronic stress and may have an influence on oestrus behaviour, prolonged parturition and a higher number of stillborn piglets. In this study, a response test towards a stockperson was evaluated for improved maternal behaviour and increased piglet survival. Records were available from 638 German Landrace gilts with 860 observations tested for the response to an observer in the familiar environment of the mating centre. The degree of response was scored in five ordered categories. Fertility information (number of piglets born alive and stillborn) was available from 293 sows. The figures for survival rate and crushing by the sow were used from 2408 piglets. The estimated heritability in the human response test was h2 = 0.09. Gilts which displayed only low response to humans showed fewer stillborn or crushed piglets in their first litter. The conclusion of this study was that the measurement of gilts responses to humans could be collected under production conditions since the gilts were tested in their home pens. The estimated additive genetic variance indicates that there is enough variance for selection. The scoring gives some evidence that sows with low responses to an observer have an improved piglet survival rate. The data also indicated that totally unresponsive sows had a higher number of stillborn piglets.

For more information the full article can be found at http://journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/applan/issues

Pain and discomfort in male piglets during surgical castration with and without local anaesthesia as determined by vocalization and defence behaviour

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Surgical castration of male piglets without anaesthesia is routine in domestic pig production causing serious distress and impairment of welfare. Thus, the EU is seeking alternatives, with local anaesthesia being one of the possible candidates. The aim of the present study was to compare surgical castration without anaesthesia (castration by cutting the spermatic cords (C) with castration under local anaesthesia (CL), the act of intratesticular anaesthesia (L), and the combined effect of local anaesthesia and the following castration (L + CL) under practical field conditions on a commercial farm. Distress was estimated according to a set of behavioural indicators derived from vocalisation and defence movements of the piglets. C had the overall worst effects on the indices, made up assumingly by the pain due to the intensity and duration of the procedure, although it was not possible to separate the effects of handling and the procedure of castration. Local anaesthesia reduces the intensity of pain experienced during castration as assessed by changes in the behavioural indicators used here. But this positive effect was partly obscured by additional distress due to prolonged handling. It is concluded that the welfare benefits of local anaesthesia for castration of piglets, as carried out and assessed here, may not fully meet expectations, and that further research is needed to find ways to reduce the suffering of male piglets, that it is necessary to castrate.

For more information the full article can be found at http://journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/applan/issues

Autonomic reactions indicating positive affect during acoustic reward learning in domestic pigs

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Cognitive processes, such as stimulus appraisal, are important in generating emotional states and successful coping with cognitive challenges is thought to induce positive emotions. We investigated learning behaviour and autonomic reactions, including heart rate (HR) and its variability (standard deviation (SDNN) and root mean square of successive differences (RMSSD) of a time series of interbeat intervals). Twenty-four domestic pigs, housed in six groups of four, were confronted with a cognitive challenge integrated into their familiar housing environment. Pigs were rewarded with food after they mastered the discrimination of an individual acoustic signal followed by an operant task. All pigs quickly learned the tasks, while baseline SDNN and RMSSD increased significantly throughout the experiment. In reaction to the signals, pigs showed a sudden increase in HR, SDNN and RMSSD, and a decrease in the RMSSD/SDNN ratio. Immediately after this reaction, the HR and SDNN decreased, and the RMSSD/SDNN ratio increased. During feeding, the HR and the RMSSD/SDNN ratio stayed elevated. The pigs showed no cardiac reaction to the sound signals for other pigs or their feeding pen mates. We concluded that the level of cognitive challenge was adequate and that the observed changes in the autonomic tone, which are related to different dimensions of the affective response (e.g. arousal and valence), indicated arousal and positive affective appraisal by the pigs. These findings provide valuable insight into the assessment of positive emotions in animals and support the use of an adequate cognitive enrichment to improve animal welfare.

For more information the full article can be found at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00033472

Domestic pigs, Sus scrofa, adjust their foraging behaviour to whom they are foraging with

Posted in: Environment, Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Subordinate domestic pigs show behavioural tactics similar to the ones described as tactical deception in primates and corvids (i.e. crows, ravens and jays) when foraging with scrounging dominants for a single monopolizable food source. Here we investigated further whether they can learn deceptive tactics to counter a scrounger by first retrieving the smaller of two hidden food baits, and whether they can discriminate between different types of co-forager. Seven subordinate pigs were tested with co-foragers, and also alone, when foraging for two differently sized food baits hidden in two of 12 buckets in a foraging arena. Unlike their co-foragers, the subordinates already knew where the foods were located; co-foragers differed in whether they were scroungers or not. Subordinates did not respond to scrounging with the predicted deceptive tactic of visiting the small bait first. They did, however, lose their overall preference for retrieving the large bait first and increased their foraging speed compared to when foraging with nonscroungers or on their own. The findings suggest the ability to discriminate between different individual co-foragers in domestic pigs, and increasing foraging speed as a way of responding to exploitation by scrounging dominants in competitive foraging situations with several food patches.

For more information the full article can be found at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00033472

Antibiotic-free pork production can be profitable

Posted in: Meat Quality, Production, Welfare by admin on July 14, 2011 | No Comments

As the market for pork becomes more and more differentiated, retailers and processors are looking for opportunities to meet the demand from consumers for products which meet their aspirations in terms of welfare, food safety and the environment. This trend is well-developed in Europe where there is a wide range of pork categories such as outdoor reared, antibiotic free and organic. Now antibiotic-free pork production is increasing significantly in the USA. The question for producers is whether any loss in production efficiency and the additional costs involved are offset by the price premium received. European experience suggests that the additional cost per pig is in the region of $5.24. However, a paper presented at the recent American Association of Swine Veterinarians by Darwin Kohler, James Schneider, and Chad Bierman demonstrated that removal of antibiotics on one farm did not lead to a significant loss of performance.

“The use of antibiotics in livestock feeds is meeting with increasing opposition,” note the authors. “The controversy revolves around the level of antibiotic fed to livestock for non-therapeutic use, which in turn causes an increase in bacterial resistance in humans and known allergic reactions or toxicity.” The consumers of meat products today are asking for a more ‘natural’ food product.

European opposition has been stronger than in the US. A ban of over-the-counter antibiotics was implemented in Sweden in 1986, Norway in 1992, Finland in 1996, Denmark in 1998, and Poland and Switzerland in 1999. Current EU regulations state that antimicrobials used in either human or in veterinary therapeutic medicine are prohibited from use as feed-additive growth promoters in livestock.

Based on experience in Sweden and expert opinions, the likely performance effects of removing antibiotics and the cost implications are shown in Table 1.

Table 1: Technical assumptions of antibiotic ban

Trait Most likely change

PSY Decreased 1 pig

Weaning age Increased 1 week

Wean to 25kg Increased 5 days

FCR 25-114kg Increased 1.5%

Pre-wean mortality Increased 1.5%

Grow/finish mortality Increased 0.49%

Net additives cost Increased $0.25/pig

Total cost/pig Increased $5.24/pig

Today, one form of antibiotic free (ABF) pork production is beginning to be used in the United States, note the authors. It is based on no birth-to-market antibiotic use of any kind, no growth promotants, no natural or artificial hormones, no ionophores, no animal proteins and no animal by-products. “Can antibiotic free (ABF) pork production be more successful in the United States than indicated in Table 1?” they ask.

Case study farm shows little effect on performance

The case study reported in the paper is a 1,000-sow farrow to finish conventional confinement system. This system has been closed to live animal introduction since 1996. Management was interested in pursuing ABF pork production. Small amounts of antibiotic had been used or needed in their herd, and a premium was being offered for antibiotic free pork. Pigs are vaccinated for Mycoplasma hyopneumoniae and the herd is PRRS stable. Gilts are raised internally and there is an off-site boar stud. Since December 2004 no antibiotics, growth promotants, or animal by-products have been used in pigs from birth to market. The farm maintains records of inoculations, illnesses and injuries, treatments, etc. Very few pigs require treatment. If prohibited medication is used in treatment, the pigs are marked for identification and are sent to conventional markets. “Products such as zinc, copper, probiotics, enzymes, botanicals, enzymes, mannan oligosaccharides, egg antibodies, oil of oregano, and organic acids are allowed to be used in place of antibiotics in the ABF program,” explain the authors. “However, these products are not necessary in this herd and are not in use as replacements for antibiotics.”

Table 2 shows the sow herd performance before and after ABF. The ABF program does allow for antibiotic usage in the sow herd. Antibiotic usage in the sow herd changed little over the six-year period. Comparisons of traits between the ‘before ABF’ and ‘after ABF’ periods are both positive and negative and show no consistent advantage to the use of antibiotics. Pigs had received an antibiotic at birth before ABF. The expectation would be an increase in pre-weaning mortality. An increase from 8.2% to 9.9% did occur but was not reflected in pigs weaned per mated female per year. Adjusted 21-day litter weaning weight is 13 pounds (5.9kg) heavier after ABF with an increase in pounds weaned per sow per year of 8%. Only pre-weaning mortality was in agreement with the negative predictions shown in Table 1.

Table 2: Sow herd performance before and after ABF production

Before ABF After ABF

Jul 02 – Dec 04 Jan 05 – Jun 07

Average total pigs/litter 11.4 11.4

Average pigs born alive /litter 10.4 10.6

Pre-wean mortality (%) 8.2 9.9

Average age at weaning 18.2 20.5

Farrowing rate 93 91.6

Litters/mated female/year 2.56 2.52

Pig wnd/mated female/year 23.8 23.8

Table 3 shows the herd’s finishing performance before and after ABF. Although previous reports show poorer performance with ABF production, few differences are noted here. Only feed conversion showed a noticeable drop in performance.

Table 3: Finishing performance before and after ABF

Grow finish trait 2002 – 2004 2005 – 2007

Av. Lwt. of pigs entered (kg) 18.2 21.1

Av. Lwt of pigs sold (kg) 114.5 118.4

Av. days to market 114.6 115.2

Av. daily feed intake (kg/day) 2.22 2.36

Av. daily gain (g/day) 839 839

Feed conversion ratio 2.65 2.69*

*Feed conversion adjusted to common entry and sale weight

The only significant difference is in FCR and the authors calculated this to add $0.68 to production cost. Finisher death loss was slightly higher after ABF resulting in a cost increase of $0.07 per market hog. Average drug cost before ABF of $0.18 per market hog resulted in a saving after ABF. Pigs were no longer sold grade and yield during the last three years therefore carcass yield and percent lean were assumed to be unchanged.

ABF premium gives bigger margins

Additional ABF premium was calculated as the difference received in harvest price by this herd versus other similar herds and selling grade and yield to the same market that this herd had been selling to before ABF. Using this method, the additional ABF premium was estimated to be $4.26 per head in 2005 and 2006. “The ABF premium tends to inversely fluctuate with the base grade and yield price and is much higher today when market prices are lower than in the previous two years, note the authors. “Current additional ABF premium for November 2007 is $16.62 per head.” Overall, taking the differences in performance and costs into account, there was a net average benefit of $7.89 for ABF production compared to the period when antibiotics were used.

Little or no differences in production numbers were observed on this farm. The increase in cost of production has been shown to be $0.32 per head. “Success is attributed to the use of appropriate genetics, maintaining a closed herd and maintaining a high level of biosecurity to keep pathogens out,” say the authors. “Good management in areas of proper husbandry, nutrition management, environmental control, prompt treatment or removal of sick pigs and attention to detail is essential.” Not only does this case study illustrate the feasibility of ABF production, but it demonstrates significant profit potential in today’s niche markets, they conclude.

Water medication systems

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Increasingly, pork production systems around the world are using drinking water as the delivery mechanism for a variety of nutritional and health related products. These products can range from acidifiers and probiotics at weaning to vaccines to antimicrobials to nutritional supplements, etc. throughout the growth process.

Delivery of these products via the drinking water system most often relies on a pump and mixing chamber to incorporate these materials into the drinking water. In the US, most medicators are based on a fixed ratio of 1 part stock solution per 128 parts drinking water.

With the increased usage of water delivered products has come an increase in the risks associated with these delivery systems. The following are common mistakes made by US producers in using water as the delivery mechanism for a variety of products.

Many products, especially vaccines, require that the pigs consume the product within 4-6 hours of reconstitution. Recent data from Iowa State University suggests that 100% of weaned pigs will visit a nipple drinker within a 4-6 hour time period beginning at 8 am. Thus, timing of delivery of the product to the drinking water is of critical importance if all pigs in a population are to receive an adequate amount of the product.

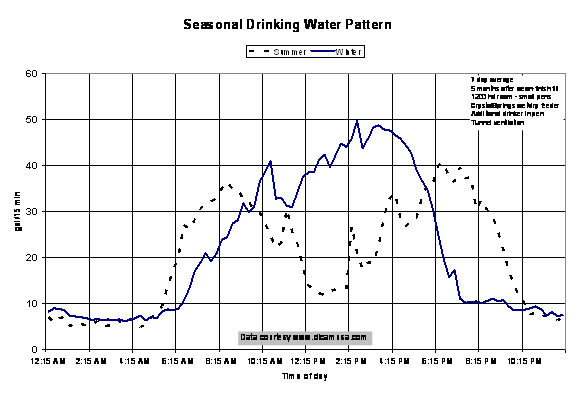

Figure 1: Effect of season on 24-hour water usage pattern in a 1200 head wean-finish facility 5 months after weaning in central Nebraska. Data courtesy Dicamusa.com

In thermo-neutral conditions, both feed and water usage generally begin increasing around 6 am in the morning, with a mid-morning peak around 10 am, followed by the day’s peak in disappearance at 2-3 pm. By 6 pm, both feed and water intake have returned to a relatively low level. There is very little feed or water intake during the night. Drinking water disappearance, and by association feed disappearance, is minimal during late evening and early morning hours.

If pigs are grown to slaughter in warm conditions (summer conditions in much of the upper Midwest), these patterns change. Feed and water intake now begins at approximately 4 am, with the morning peak at 8-9 am. This morning peak is followed by a mid-day decline in feed and water disappearance, with a resumption in intake in the early evening hours. Even in these conditions, there is limited drinking water usage during late evening or early morning hours.

In North America, commonly used water medicators are often rated at a capacity of up to 26.5 litres (7 US gal)/minute. In almost every instance, they are connected to water lines in the facilities that have a capacity of 21 liters (5.5 gal) per minute (19 mm/3/4” inside diameter piping). This suggests that the sizing of the water delivery pipes in the facility are the limit to water flow. However, it is quite common to see water medication devices connected to water delivery lines with 13 mm (1/2”) diameter hoses, which have a capacity of only 9.5 liters (2.5 US gal)/minute. A common complaint by producers who make this mistake is ‘my pigs don’t like the medicine in the water because water intake always decreases when I water medicate’. The real cause of the decline in drinking water is the restriction in water flow associated with the water medication device connection.

In North America, commonly used water medicators are often rated at a capacity of up to 26.5 litres (7 US gal)/minute. In almost every instance, they are connected to water lines in the facilities that have a capacity of 21 liters (5.5 gal) per minute (19 mm/3/4” inside diameter piping). This suggests that the sizing of the water delivery pipes in the facility are the limit to water flow. However, it is quite common to see water medication devices connected to water delivery lines with 13 mm (1/2”) diameter hoses, which have a capacity of only 9.5 liters (2.5 US gal)/minute. A common complaint by producers who make this mistake is ‘my pigs don’t like the medicine in the water because water intake always decreases when I water medicate’. The real cause of the decline in drinking water is the restriction in water flow associated with the water medication device connection.

A second common mistake is a stock solution reservoir that is too small. Many producers assume that water usage is relatively stable throughout a 24-hour period. If the pig’s drinking water usage is 4 litres (1.1 US gal) per day and there are 1000 pigs in the facility, the total stock solution required at 1:128 dilution is 31.25 litres (8.3 US gal). If the stock solution reservoir is filled twice daily, this suggests that a 16 litre (4.2 US gal) capacity reservoir is adequate. In reality, almost 70% of the drinking water is consumed from 6 am to 4 pm. If the reservoir is filled at 7 am and 5 pm, the capacity of the reservoir needs to be at least 22 (5.8 gal) litres or there is a risk that the reservoir will be empty prior to the next recharge, resulting in pigs drinking water that has no stock solution added.

Many producers fail to account for the impact of pressure regulators on water flow. If the incoming water line pressure is 275 kPa (40 psi) and a regulator is used to lower the line pressure to 140 kPa (20 psi), water flow is reduced to 71% of what it was at the original pressure. This suggests that sizing of water lines is even more important than many producers think.

Water filters are often installed in delivery lines to deal with sediment issues associated with the on-site well, etc. In some instances, the location of the filters makes them very difficult to routinely flush or clean, while in others, a routine of regular maintenance is not planned for.

Water filters are often installed in delivery lines to deal with sediment issues associated with the on-site well, etc. In some instances, the location of the filters makes them very difficult to routinely flush or clean, while in others, a routine of regular maintenance is not planned for.

Finally, don’t overlook the water meter as a flow restrictor in the water line. Many swine facility contractors install water meters with 16 mm (5/8”) orifices that have 19 mm (¾”) NPT connectors. These meters are generally $50-75 cheaper than meters with larger orifices.

Photo Captions:

Medicator-1 – Two medicators for 2400 wean-finish pigs with 125 litre (33 gal) stock solution reservoir

Medicator-2 – Water medicator rated at 26.5 litres (7 gal)/minute incorrectly connected to 19 mm (3/4”) inside diameter piping with 13 mm (1/2”) washing machine hose.

.

The effect of perceived environmental background on qualitative assessments of pig behaviour

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Qualitative behaviour assessment is an integrative methodology that characterizes behaviour as a dynamic, expressive body language (e.g. as anxious or content). Such assessments are sensitive to environmental context, which makes them informative but also vulnerable to observers’ biased views of that context. This study investigated whether and how perceived environmental background affects observers’ qualitative assessments of pig behaviour. Fifteen growing pigs were filmed individually against a neutral background while interacting with a novel object. The footage of each pig was digitally isolated from that background and pasted against indoor and outdoor backgrounds filmed in real time. The 30 video clips thus obtained were shown to 16 observers, who were led to believe these were 30 different pigs filmed in either an indoor or an outdoor pen. Free-choice profiling was used to instruct observers in qualitative behaviour assessment, and data were analysed with generalized Procrustes analysis. Analysis of variance found a significant effect of environmental background on pig scores on the second consensus dimension (confident/content–cautious/nervous), but not on the first (playful/active–bored/lethargic). However, 95% confidence intervals and indexes for the variability attributable to environmental background, calculated for both consensus dimensions, indicated that any such effects should be relatively small. High correlations were found between indoor and outdoor pig scores on both consensus dimensions (r >/ 0.95). Together these results suggest that environmental background may slightly shift, but is unlikely to seriously distort, observer characterizations of pig expression. Last, we discuss possible strategies for reducing the effect of contextual bias on qualitative behaviour assessment.

The effect of perceived environmental background on qualitative assessments of pig behaviour

Pigs learn what a mirror image represents and use it to obtain information

Posted in: Environment, Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Mirror usage has been taken to indicate some degree of awareness in animals. Can pigs, obtain information from a mirror? When put in a pen with a mirror in it, young pigs made movements while apparently looking at their image. After 5 h spent with a mirror, the pigs were shown a familiar food bowl, visible in the mirror but hidden behind a solid barrier. Seven out of eight pigs found the food bowl in a mean of 23 s by going away from the mirror and around the barrier. Naïve pigs shown the same looked behind the mirror. The pigs were not locating the food bowl by odour, did not have a preference for the area where the food bowl was and did not go to that area when the food bowl was visible elsewhere. To use information from a mirror and find a food bowl, each pig must have observed features of its surroundings, remembered these and its own actions, deduced relationships among observed and remembered features and acted accordingly. This ability indicates assessment awareness in pigs. The results may have some effects on the design of housing conditions for pigs and may lead to better pig welfare.

Pigs learn what a mirror image represents and use it to obtain information

Single dose therapies can help control disease

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Producers know all too well how quickly disease can spread in a herd, not to mention the dramatic impact it can have on their profitability. Swine respiratory disease (SRD) is costly to North American producers in terms of productivity losses, medication and labour. Clearly, controlling disease is key to running a profitable operation. Producers can take control through good preventative health management practices and by incorporating new drug therapies, such as single dose anti-infectives, into their disease protocols.

Disease treatment – Why single dose therapies?

Water and feed medications are commonly used in hog operations and certainly have their place in the treatment cycle. However, when pigs are sick, they usually eat and drink less so it can be difficult to ensure each pig receives the correct amount of medication.

Single dose therapies provide a better alternative in many cases. From a practical standpoint, when a complete treatment of anti-infective therapy is contained within a single dose, the animal gets all the medication it needs at once, saving you time and money. There is also the advantage of reduced stress on the animal. Why risk exacerbating an already sick and stressed animal by using a multiple-dose treatment when a single one is available?

By its very nature, single dose administration also ensures compliance, i.e. following veterinary recommendations. You could say that compliance is “built-in”. Not following a medication’s directions can create unnecessary problems. For example, when a sick pig begins to look better, producers may be inclined to stop treating the animal. This is an easy mistake to make, but the repercussions can be serious and may hinder the animal’s recovery and lead to relapse. Additionally, the development of antimicrobial resistance is a potential threat in under-dosed animals.

The moral of the story is that to make the most of anti-infective therapies and minimize the costs and impact of disease, it is vital to follow the correct dosage and recommended duration of therapy. These two success factors are easily achieved with a single dose product allowing you to focus on other management issues.

Disease prevention – herd health management protocols

Disease treatment will likely always be part of your routine; so should herd health management protocols. Why? Remember the old saying that an ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure. Adopting herd health management protocols can help to prevent disease from occurring in the first place and help producers and barn employees recognize the symptoms when disease does occur.

Producers can take certain steps to ensure their barn environment is as healthy as possible, minimizing the stress on animals. For example, barns should be constructed to maximize comfort including protection from drafts, moisture and variable temperatures. Animals should also have access to food and fresh, clean water at all times. Your veterinarian can provide other suggestions and assist you in developing a herd health program that’s right for your operation.

As effective as single dose therapies can be in treating and controlling the spread of disease, they only work to their full potential if a producer follows proper herd health management protocols. By doing both, you can help ensure the continued good health, performance and optimal profitability of your herd.

Dr. Don McDermid is Manager of Veterinary Services – Swine, at Pfizer Animal Health Canada

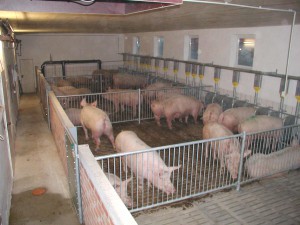

Group housing sows in Europe

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

In the UK all newly weaned and gestating sows have had to be kept in group housing systems since 1999 following a 7 year conversion period. The EU introduced legislation in 2001 that banned the construction of new individual confinement systems from 2003 and will make all existing sow stall housing illegal in 2013.

The UK legislation enforces a ban on confinement (apart from the week pre-farrowing and through to the day of weaning) and is ‘gold plated’ in comparison to the minimum requirements of the EU, which states that all sows must be kept in groups only from the 5th week of gestation up to 1 week prior to farrowing when they can be moved into the farrowing accommodation. Some other EU countries and even federal states within a country have also often ‘gold plated’ the legal requirements well in excess of the basic requirements. Pressure is beginning to build up for a ban on farrowing crates with some UK supermarket chains now demanding that all pig meat should be sourced from herds that do not use confined farrowing facilities.

The good news is that there are now herds operating across Europe achieving in excess of 30 pigs weaned per sow per year using group housing systems and weaning at around 33 days.

The UK’s early conversion, followed closely by its pig meat suppliers Denmark and Holland, has provided some examples of what can be achieved with group housing systems. It has been absolutely clear that the key to any sow housing system is the feeding method employed and in fact there are as many feeding system variants as there are potential housing solutions.

The situation also differs across Europe, with family farms and no employed labour in areas such as western and southern Germany, whilst in the eastern areas of Germany there are larger herds (>300 sows) run entirely with employed labour. The (usually) smaller family farms will probably be considering either to expand or sell up and no longer produce pigs, whilst the larger units with employed labour will be considering the viability of converting relatively large existing slatted floored buildings, albeit often with limited financial reserves and with the need to provide a viable system for 300 or more sows and the employed work force. The solution for a smaller family farm intending to expand will certainly differ considerably from an existing large breeding unit. However, both will have to initially consider the system they will adopt based on the feeding system and whether they will operate a ‘static’ or ‘dynamic’ sow group during gestation.

There has been a trend for larger units to run batch farrowing systems based on farrowing only every third, fourth or even fifth week. This produces very large group sizes and therefore suits the management of the large static groups. The management routine will then operate around weeks where farrowings are planned and other weeks where weaning and mating (usually A.I.) are concentrated. This has implications for the sow housing and farrowing accommodation, as well as the work routine for the animal attendants and management. Management discipline needs to be first rate.

Herds operating a weekly or fortnightly farrowing sequence will often consider either a large dynamic group where animals are added in at weaning or after they are confirmed pregnant (the 5th week), spending this initial period in individual confined housing or small service groups. Static groups are also sometimes built up over several weeks in smaller and medium sized herds with sows added to the group at weaning/mating or once confirmed pregnant. This leads to an increased risk of aggressive behaviour and returns to service.

Where static groups are kept in smaller herds farrowing weekly or fortnightly, then they are often in groups of 4 to 8 sows. A range of systems are commonly used in Europe for such static groups and these include:

Free access feeder stalls with a communal pen, which can be partly slatted or straw bedded. Most countries, or federal states (when applicable) within individual countries, will often insist on the provision of a solid floored bedded area with access to edible/chewable bedding in slatted systems. The sows are usually fed automatically (rationed as a group) with either dry or liquid feed. These facilities will often be fitted into an existing individual stall house or a purpose-built new building. When converting old or existing housing it is important to consider that the overall stocking density may be reduced and in very cold northern parts of Europe supplementary heating is often included, along with modifications to the ventilation system. Straw bedded and part/fully slatted versions are also found.

Kennel systems are also being used increasingly in the colder areas of mainland Europe and these have long been popular in the UK. They are quite simply either individual lying kennels or now, more commonly, small low-roofed insulated kennels or huts (similar to outdoor pig huts) where the sows rest and sleep in small groups. They can be either under a roof or partly in the open, but have natural ventilation. The dunging and exercise yard can be solid or slatted. Huts can have insulated floors without much bedding (some must usually be provided even in slatted housing) or be straw bedded and cleaned out using a tractor/mechanical scraper.

Both of these kennel systems, straw bedded yards and partly slatted environmentally controlled pens, can also be fed in individual feeders (one per sow or on a cafeteria system). These are usually found on existing pig units as they are extremely expensive when built in from new. The individual kennel variant even allows for them to be fed in the individual kennel or cubicle and this is often combined with the daily mechanical removal of solid manure from a solid straw based run.

The “Kombifeeder” is an individual feeder that can be used as a stall for the first 4 weeks of gestation. This approach is favoured on smaller units where they want to ensure the sows do not mix for the first part of gestation when they may still be confined all of the time. Subsequently it can be used as an individual feeder and the sows can lie in them (albeit with no automatic gate at the rear to protect them).

The “Vario-Mix” or “Time-Mix” type feeder has one or more feeding spaces with electronic controlled feeding located in the exercise/dunging area. The feeder drops small portions of feed (usually 20-25g in the case of dry feed or 150g of wet feed) at each drop and can be fitted to feed a small static group of 5 to 8 sows per feeder. The sow triggers either a mechanical or electronic switch and effectively has to root for food. A computer can be used to control the portions and the times the feed is available. This system is found on large herds in Europe (up to 750 breeding sows), but it also fits well into smaller herds. It is best suited for groups of between 5 and 30 sows (1 to 4 feeding points). However, some sows do not respond to these system and these will have to be catered for in alternative accommodation.

Other variants of these feed stations include the tube wet feeder (“Breinuckel”) where the sow is recognized by a transponder and fed according to the ration programmed into the system. The sow only has shoulder barriers for protection and is fed through a metal tube. It is recommended that of these feed stations can provide for a maximum of 18 sows.

The Belados feeder is in effect an electronic feed station without a feeding stall. This is based either on an existing liquid feeding system or alternatively it can be fitted with its own feed and water mixing tank. It is claimed that about 30 sows can be fed per station. These two wet feeding hybrids of the single space and EFS feeder are not yet widely used and experience is limited.

Trickle feeders can also be used with kennels for large and small static groups in straw based or slatted pens in a new or converted building. It is important to ensure that there are about 15% more feeding spaces available than are theoretically required in order to ensure that varying batch sizes can be managed successfully. Not all animals appear to cope with the trickle feeder system, even though the majority do. Some alternative arrangements need to be made for maybe 5% of the gestating herd.

Drop feeders are similar to trickle feeders, except the feed is delivered to all individual animals in one drop from a volumetric hopper or tube. There is also a very effective wet feed variant, the ‘Quickfeeder’ that drops the feed into a trough maintained with a fixed water level. Sows fed wet feed tend to exhibit less aggression during feeding because the slower eating pen mate has a better chance to consume a full ration more quickly, therefore there appears to be a more even intake.

The EFS (Electronic Feeding Station) system is well known and is the feeding method often seen as fitting in best with the so-called dynamic group housing system. These are usually based on large pen variants containing 60 to 200 sows with individual transponders in one dynamic group, with usually 2 to 4 EFS stations. The EFS system can involve a two-pen variant where the sows move from one pen into the other via the feeding station. The sows are moved into the pen that allows entry to the feeder by the opening of a gate once daily (usually first thing in the morning). The advantages are claimed to be less aggression and easier supervision of animals that fail to feed. Gilts are usually either placed into the large dynamic group immediately after first mating or penned separately until after their first weaning. Management and supervision ability and demands must not be underestimated. EFS systems have high maintenance and repair needs and transponders must stay in place for the system to deliver top performance.

Dump or spin feeders are quite popular in the UK, but are almost completely absent on mainland Europe. These can be used to feed both fixed and dynamic groups of various sizes. The pens are usually straw bedded and some EFS users have actually removed their old EFS feeding stations and replaced them with dump or spin feeders. Both of these drop the feed over an area sufficiently large to ensure a reasonably even feed intake. The spin feeder is intended for a larger area and usually for a large group. Despite evidence of good performances achieved by herds using these methods, European advisors and their pig producing customers are concerned about the problems of feed wastage and potential aggression.

Liquid feeding of gestating sows in a long trough with (and even sometimes without) shoulder barriers can also be used for a range of usually small to medium sized static groups. Liquid feeding offers a tremendous advantage in ensuring more even feed intakes and thus maintaining more even sow body condition scores.

Ad-lib feeding of gestating sows, using a high fibre diet, is a recent trend in the Netherlands. Good results are claimed for this approach for both static and dynamic sow housing systems. They employ ad-lib single space feeders filled automatically. This system demands low nutrient density high fibre rations that match the sow’s voluntary feed intake with her nutrient needs. Unfortunately, these special feeds cannot be formulated economically in many areas of Europe as they are based on high fibre raw materials not universally available.

Neville Beynon is a UK-based consultant who works extensively in continental Europe

Photo captions:

- Kombifeeder – The Kombifeeder is an individual feeding stall that can be used as a confinement stall for the first 4-5 weeks of gestation

2. Quickfeeder – The Quickfeeder drops liquid feed into a trough that contains a fixed level of water