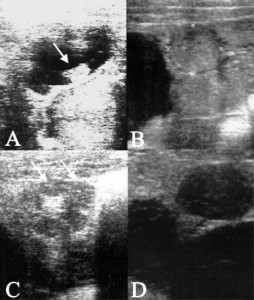

In Europe, ultrasonography – for which the term “scanning” is used – has been implemented increasingly on swine production units. This technique is usually performed through the skin, usually of the abdomen, without the need to penetrate the animal via the rectum, as is the case in horses or cattle (Figure 1). The main purpose for scanning pigs is to test for pregnancy, indeed, scanning is superior to other methods of pregnancy diagnosis. The main advantage is that it allows for early use (starting day 20/21 after breeding; Figure 2A), combined with its accuracy at even this early stage of pregnancy (close to 100 %). The main disadvantage is the relatively high price of the equipment although, over recent years, prices have decreased dramatically and good machines are currently available for a reasonable cost.

However, scanning offers more than merely testing for pregnancy. With ultrasonography, both the non-pregnant uterus (Figure 2B) and the ovaries (Figure 2C) can be visualized. Imagine the many situations when you wanted to have a look inside the animal but failed for obvious reasons. Using ultrasound, gilts and sows are now virtually transparent! Besides pregnancy testing, this unique form of ultrasonography can be used for multiple purposes in breeding pig facilities. Those purposes are:

1. Checking the ovulation process: The ovary and all the ovarian structures that appear around ovulation are well described. This allows for checking when ovulation occurs in individuals and in groups of breeding sows. Scanning to check for ovulation is useful whenever there are questions relating to the breeding management and timing of insemination in particular.

2. Checking for puberty (i.e. sexual maturity): As the pig matures sexually and changes from the pre-pubertal to the pubertal stage, there is uterine growth and the gilts commence their cycling activity, with the first ovulation and subsequent development of corpora lutea or “yellow bodies” in the ovary. Scanning allows for the visualization of the uterus and the ovaries in both the pre-pubertal and the pubertal gilt and the assessment of both organs can give valuable information on sexual maturity. If the ovary is scanned, animals having only small follicles are considered pre-pubertal, while those having large, pre-ovulatory follicles or ovarian structures indicating completed ovulation (corpora lutea) are pubertal. If the uterus is used for assessment, the uterine size has proven to be a reliable measure of whether gilts are pubertal or not. In order to make this assessment, the uterus has to be imaged as a cross-section, then measured in two dimensions and the cross-sectional area calculated. Pre-pubertal gilts have a cross-sectional area of ≤ 1cm2, while it is ≥ 1.2cm2 in pubertal animals. Though separate assessment of either the ovaries or the uterus gives almost 100% correct diagnoses, maximum accuracy is achieved if the assessment involves both organs concurrently. Scanning to check for puberty might be desired in case of low gilt performance, in terms of low conception rates or small litter sizes.

3. Examination of females with reduced or complete cessation of fertility: If a female displays reduced fertility or absence of fertility, this can be for different reasons. Scanning is directly helpful if the reason is the female herself, with defects related to the ovaries and/or the uterus. Ovarian cysts are usually considered one main reason for the animals’ failure to breed. However, it is only polycystic ovarian degeneration (POD), where the ovary has only cystic ovarian structures, which is fatal to fertility, while single or multiple cysts accompanied by “normal” ovarian structures are more frequent but of lesser significance. Cysts can indeed be identified using ultrasonography, (Figure 2D) and females with POD quickly culled, thereby reducing the number of non-productive days. Amongst females exhibiting fertility problems, many have uterine infections such as inflammation of the endometrium or lining of the uterus. Although the chronic inflammation is more prevalent, the acute type can sometimes be observed combined with a purulent vaginal discharge. Unfortunately, scanning allows only for the detection of acute endometritis, and recognition usually occurs on the basis of abnormal flocculent or clotted fluid within the uterus.

The echotexture is another parameter used to describe the appearance of the uterus in ultrasound images and uses the distribution and frequency of lighter and darker areas for description. The echotexture can be described as homogeneous or heterogeneous and undergoes normal physiological changes during the oestrus cycle. It is heterogeneous when females approach or are in heat and larger follicles are present, and homogeneous at any other stages of the oestrous cycle, for example when corpora lutea are present. Any deviation from the physiologically normal status might be considered abnormal and is associated with reduced fertility. A third parameter, uterine size, might also be helpful in assessment of whether a uterus is functioning normal or not. The size is determined as described for gilts and is given as the sectional area. Uterine size has been shown to correlate with uterine weight and the weight itself helpful in the diagnosis of uterine disorders. For instance, the mould toxin zearalenone, which can cause reproductive problems in pigs, has been associated with very small (light) and very heavy reproductive tracts.

With its multipurpose usage potential, ultrasonography can be much more than merely a procedure to test for pregnancy. Given that pregnancy diagnosis may be performed on day 20 or 21 after breeding, non-pregnant females can be detected right at the time they are presumed to return to service, so they can be subjected to very close heat detection supervision. The concurrent assessment of the ovaries and the uterus in these non-pregnant females gives additional benefit. As mentioned before, animals with POD can be culled immediately. However, as a number of non-pregnant animals will have corpora lutea or small follicles, producers might be willing to treat them hormonally to induce oestrus and/or ovulation. Finally, animals with obvious uterine alterations, such as abnormal intrauterine fluid or atypical echotexture and thus reduced fertility, can be quickly sent to slaughter. This entire procedure, in combination with routine pregnancy testing, including ovarian as well as uterine diagnosis, will certainly increase productivity through the reduction of non-productive days.

Johannes Kauffold (Email: kauffold@vet.upenn.edu) and Gary Althouse(Email: gca@upenn.edu) are at the Department for Clinical Studies, New Bolton Center, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of Pennsylvania and Neville Beynon is with Veyx Pharma and based in the UK, (Email: nevillebeynon@ntlworld.com.)

Figure 1: Procedure of transabdominal ultrasonography of pigs. A linear transducer is placed horizontally just above the last pair of teats onto the ventral right abdomen (1A).

Figure 2. A): Image obtained from a gravid (pd+) pig showing an example of a uterine cross-section containing embryonic fluid and the embryo itself (arrow) on day 20 after breeding. B) Cross-sections of an ingravid (non-pregnant) uterus. C) Ovary with several corpora lutea. Two are marked with arrows. D) Ovary with large follicular cysts (black “pockets”).

Figure 2. A): Image obtained from a gravid (pd+) pig showing an example of a uterine cross-section containing embryonic fluid and the embryo itself (arrow) on day 20 after breeding. B) Cross-sections of an ingravid (non-pregnant) uterus. C) Ovary with several corpora lutea. Two are marked with arrows. D) Ovary with large follicular cysts (black “pockets”).