Eye on Research – The effect of space and group size on finisher performance

Posted in: Prairie Swine Centre, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on July 14, 2011 | No Comments

With the current shift in the industry toward housing pigs in groups of 100 to 1,000 per pen, questions have been raised as to whether pigs can perform as well in large groups as they do in small ones. Recent work at the Prairie Swine Centre examined how housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations affects production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables. The studies looked at the effects of small (18 pigs) vs. large (108 pigs) group sizes provided with 0.52 m2/ pig (crowded) or 0.78 m2/pig (uncrowded) of space on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Pigs in the crowded groups spent less time eating over the eight-week study than did pigs in non-crowded groups. However, average daily feed intake (ADFI) did not differ between treatments. Overall, ADG of large-group pigs was 1.035 kg/day, whereas small group pigs gained 1.073 kg/day. Average daily gain differences between the group sizes were most evident during the first two weeks of the study.

The investigation found that, over the entire study, large groups were less efficient than small groups. Although large-group pigs had poorer scores for lameness and leg scores throughout the eight-week period, morbidity levels did not differ between the group sizes. Minimal changes in postural behaviour and feeding patterns were noted in large groups.

An interaction of group size and space allowance for lameness indicated that pigs housed in large groups at restricted space allowances were more susceptible to lameness. Although some behavioural variables, such as lying postures, suggested that pigs in large groups were able to use space more efficiently, overall productivity and health variables indicate that pigs in large and small groups were similarly affected by the crowding imposed in this study.

The trial indicated no difference in the response to crowding by pigs in large and small groups. Little support was found for reducing space allowances for pigs in large groups.

WHJ comment: There is no doubt that the North American pork industry has enthusiastically embraced large group grow-finish systems in order to obtain the benefits of auto-sorting equipment, which leads to more optimal market weights and saves labour. However, little is known about the implications for pig performance and welfare. This study suggests that space allowance has a bigger effect on growth than group size, although ADG was better for the small groups. The suggestion that pigs in large groups make better use of space and therefore need less space per pig seems to be disproved by this work. Even though there are disadvantages in both performance and some measures of welfare, the trend towards large groups is likely to continue due to the magnitude of the benefits.

Reference: B. R. Street and H. W. Gonyou. – Effects of housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

J. Anim Sci. 2008. 86:982-991. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0449

Danes average 25psy but sow longevity a problem

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Danish pig producers reached the milestone of an average 25 pigs per sow during 2006/7, and that’s the figure for 30kg pigs produced, not numbers weaned per sow. However, sow longevity continues to be a problem, with an annual sow replacement rate of over 50% and sow death loss at a staggering 15%. Producer organization Danish Pig Production (DPP) is carrying out research which, it is hoped, will lead to a substantial reduction in sow wastage, according to its Annual Report.

Overall breeding herd performance averaged 24.9 pigs/sow/year, with the top 25% of producers reaching 27.8. Liveborn piglets averaged 13.5, with the top 25% of herds producing 14.0 per litter. However, the average number of stillbirths per litter remains high, at 1.7 per litter. Weaning age is around 30 days and weaning weight averages 7.3kg.

The Danish breeding program continues to focus on improving the number of piglets alive at five days of age (called LP5) and this strategy has been producing excellent productivity gains. Over the 4 years to 2007, there was a 0.34 pig increase each year in Landrace sows and 0.38 in the Large White breed. Recently, there has been much more emphasis on increasing sow longevity, defined as the number of litters produced per sow lifetime, which is included in the breeding objectives. Because this cannot be defined until the sow is culled, other measures are being used as an indication of longevity. One of these is conformation, which has been used for many years. More recently, the ability of gilts to reach breeding after weaning their first litter has been used and this is highly correlated with sow longevity. The Danish report notes that the genetic traits for carcass lean content and daily gain are negatively correlated with longevity, whereas conformation is positively correlated. These relationships are now being used when estimating breeding values for longevity.

An increase in the incidence of shoulder ulcers in sows has prompted DPP to launch an investigation to find out whether there is a genetic variation or resistance to shoulder ulcers and whether the incidence can possibly be reduced by genetic means. In the meantime, the DPP report stated that it wants to see the number of reported shoulder ulcers halved and entered into an agreement with the Danish Veterinary Association to try to achieve this. The herd vet must regularly check the prevalence of ulcers and, if this is high or increasing, formulate an action plan with preventive measures. DPP is also looking at the influence of types of treatment, nutrition and design of housing on shoulder sores. The use of rubber mats has been shown to reduce the incidence and severity of ulcers.

A reduction in sow mortality is also a key aim of DPP research to increase longevity. It points out that a high death loss is not necessarily an indication of poor sow welfare in a herd. Many sows that have to be destroyed today would have been sent to slaughter five years ago, DPP notes. Sow mortality, it says, is reduced through prompt intervention, good prevention and consistent handling of unthrifty, sick and injured sows.

A reduction in sow mortality is also a key aim of DPP research to increase longevity. It points out that a high death loss is not necessarily an indication of poor sow welfare in a herd. Many sows that have to be destroyed today would have been sent to slaughter five years ago, DPP notes. Sow mortality, it says, is reduced through prompt intervention, good prevention and consistent handling of unthrifty, sick and injured sows.

Hospital pens must be used early on to minimize the recovery period. It has initiated a demonstration project involving 20 farms around the country where data on sow longevity will be gathered and the measures that lead to improvements identified, so that this information can be communicated to producers. Hospital pens for sows are a key weapon in the fight for higher longevity. Trials have shown that it is possible to reduce the percentage of sows that die or have to be destroyed if there sufficient hospital pens available and a treatment strategy is drawn up by the vet. Preliminary results suggest that lameness was the primary cause (75% of sows) for transfer to a hospital pen. Sows stayed in the hospital pen for an average of 22 days and 80% of sows were able to return to the gestation pens or move to the farrowing house. Of the sows that were due for culling, there were 25% fewer deaths or destroyed sows.

With high and increasing litter size the use of nurse sows is very common in Denmark and DPP has investigated many aspects of this practice. A recently reported trial looked at whether the use of Oxytocin after foster piglets have been placed on the sow affected piglet growth and survival. One-step nurse sows were compared with two-step nurse sows and sows that only suckled one litter. Oxytocin was given ten minutes and three hours after new piglets were placed on the nurse sow. The first successful suckling occurred after 5.6 hours for the nurse sows that did not receive Oxytocin and 6.3 hours for the treated sows. The report notes that 50% of sows stood up during the Oxytocin treatment and suggested that this could be the reason why treatment did not help to make sows accept the piglets more quickly. Piglets weighed 100 grams less at weaning for every hour’s delay between introduction to the sow and suckling. However, there were no differences in survival rate or weaning weight between the two groups.

DPP has also compared the impact of being a nurse sow on subsequent performance, comparing one and two-step nurse sows with those that suckled just one litter. One-step nurse sows had an average 51-day period, two-step sows had 32 days and sows that were not used as nurse sows suckled for 27 days. Nurse sows took an average of one day longer to come on heat after weaning, which the authors suggest could be due to loss of condition in the long lactation period or because the sows showed heat during lactation. They also tended to have a lower farrowing rate but the one-step sows had a significantly higher subsequent litter size. The report suggests that the lower farrowing rate may be because nurse sows do not suckle for 3-12 hours after piglet introduction, which can induce a “weaning heat”. These sows have a much more variable onset of post-weaning estrus and therefore staff in the breeding area should be made aware of the nurse sows so they can pay special attention to heat checking and serving them when in standing heat.

Photo caption: SowShoulderPad-2 – Shoulder sores are a major problem in Danish breeding herds and pads like this one are used for protection

Scientific review will help to define new pig transport standards

Posted in: Meat Quality, Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is currently in the process of revising existing regulations on the transport of animals, which have not been substantially updated since 1975. However, industry practices have changed considerably since then and new scientific research has given us a better understanding of what is required to ensure the humane treatment of animals during transport.

The Canadian Food Inspection Agency (CFIA) is currently in the process of revising existing regulations on the transport of animals, which have not been substantially updated since 1975. However, industry practices have changed considerably since then and new scientific research has given us a better understanding of what is required to ensure the humane treatment of animals during transport.

The World Organization for Animal Health will also soon adopt the first ever global standards for the transport of live animals, including pigs. Ensuring that transport industry standards meet international norms is critical for a country like Canada which exports about half its annual production – including nearly 10 million live hogs a year.

Drs. Al Schaefer and Clover Bench, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientists in Lacombe, Alberta have been coordinators of a review of the existing recommendations, standards, laws and regulations on pig welfare during transport, to compare them with current scientific literature that started in 2005. This review will help ensure the upcoming changes to Canada’s Livestock Transport Code of Practice are based on scientific data to improve the welfare of animals and, subsequently, maintain or improve meat quality.

Drs. Al Schaefer and Clover Bench, Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada scientists in Lacombe, Alberta have been coordinators of a review of the existing recommendations, standards, laws and regulations on pig welfare during transport, to compare them with current scientific literature that started in 2005. This review will help ensure the upcoming changes to Canada’s Livestock Transport Code of Practice are based on scientific data to improve the welfare of animals and, subsequently, maintain or improve meat quality.

“The events that affect animals, like transport stress, are linked directly to actual outcomes in meat quality, food safety and animal welfare,” notes Dr. Schaefer. “Stress causes a number of physical changes in precisely the things that affect food flavour and quality.”

His team specifically examined loading density and journey duration standards (including rest periods and the supply of food and water) in The Recommended Code of Practice for the Care and Handling of Farm Animals –Transportation and the Canadian Health of Animals Act. The review also examined recommendations and regulations in a number of other countries, including the USA, Australia, Ireland, the UK and other EU countries.

Loading density standards

At lower space allowances, pigs encounter higher ambient temperatures, decreased ventilation and air quality, as well as insufficient space to lie down in transit. At the other end of the spectrum, increased space allowance reduces vehicle temperature and increases ventilation, but it can also increase the incidence of fighting and aggression in transit.

Overcrowding can result in increased mortality rates, food safety concerns, and reduced meat quality (primarily the incidence of pale-soft-exudative (PSE) meat). Space allowances above 0.45-0.5 m2/100 kg pig can increase skin damage and the incidence of dark-firm-dry (DFD) meat.

Proper pig density can offset the effects of high temperatures by providing adequate ventilation through vehicle vents, regulating heat production within the vehicle, and providing animals with adequate space to accommodate their size, behaviour and positions during transport.

“The effect of extremely hot and extremely cold conditions during transport and its effect on loading density also needs to be studied in greater detail,” say Dr. Schaefer. “This is of particular importance in Canada due to the extremes in temperature which are experienced throughout the country and over the course of a year.”

Travel duration

The scientific literature has yet to reach a consensus on maximum transport times or the precise impact of rest periods during transport, both of which can affect meat, points out Dr. Schaefer. In fact, he says, there is one school of thought that says short journeys may be more detrimental – for instance higher mortality rates due to animals being unable to adjust to transport stress – than for longer ones and every effort to attenuate such stress during short transport journeys should be made.

The loading and unloading of animals is the most stressful component of livestock transport. Unloading animals for rest periods mid-transport may increase the stress experienced by transported animals. “Research on loading and unloading during long distance travel and the methods used to load and unload animals is urgently needed from the point of view of animal welfare and meat quality,” says Dr. Bench. “Further studies need to determine if it would be better to allow animals to remain on the transport truck and continue their journey, with access to food and water on a ‘higher standard’ vehicle, or if it would be better to transport them shorter distances on a ‘basic’ vehicle and unload them for a rest period with access to food and water.”

“As consumers globally increasingly demand higher standards for the welfare of animals both in their rearing and transport, we must maintain the highest standards of animal welfare or risk losing market share to countries that have implemented increasingly rigorous regulations,” concludes Dr. Schaefer.

Photo captions:

Al Schaefer – Al Schaefer, from Lacombe Research Station, one of the authors of the transport review

Trucking pigs – Livestock transport practices have changed and regulations are in need of updating

Remodelling expands Big Sky sow base

Posted in: Environment, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Complete remodelling of 600-sow farrow to finish barns into 1800-sow units producing isowean pigs is the route to expanding the sow base at Humboldt, Sask. based Big Sky Farms, which currently has 49,000 sows. And, says production manager Richard Johnson, it will cut overhead costs per sow leading to a lower cost per piglet produced. The company purchased the assets of Community Pork Ventures (CPV) in 2005, a production system that had been based on 600-sow farrow to finish barns, with four units in the 12,000 sow operation holding 1200 sows. However, the Big Sky production model was based on three-site production, with large-scale breeding units, off-site nurseries and contract finishing barns. “As we got to know and work with the CPV system, we thought there was an opportunity to expand and/or retrofit the systems, which in turn would give us a greater return on capital invested,” explains Johnson. “Not only can we spread our central overhead and management costs over more sows but the specialization in just breeding and farrowing leads to better results.”

Complete remodelling of 600-sow farrow to finish barns into 1800-sow units producing isowean pigs is the route to expanding the sow base at Humboldt, Sask. based Big Sky Farms, which currently has 49,000 sows. And, says production manager Richard Johnson, it will cut overhead costs per sow leading to a lower cost per piglet produced. The company purchased the assets of Community Pork Ventures (CPV) in 2005, a production system that had been based on 600-sow farrow to finish barns, with four units in the 12,000 sow operation holding 1200 sows. However, the Big Sky production model was based on three-site production, with large-scale breeding units, off-site nurseries and contract finishing barns. “As we got to know and work with the CPV system, we thought there was an opportunity to expand and/or retrofit the systems, which in turn would give us a greater return on capital invested,” explains Johnson. “Not only can we spread our central overhead and management costs over more sows but the specialization in just breeding and farrowing leads to better results.”

The first unit to undergo the transformation was the company’s Kelsey barn, located near Melfort, Sask. Additional sow pens were made by modifying the existing part slatted finishing rooms, which had pens of 23 pigs. Three pens were made into one, although the pen divisions between the lying areas were left in place. Each pen now holds 30 sows, which are fed on the floor using volumetric drop dispensers. One of the finisher rooms was left with 12 small pens in order to house sick, lame or thin sows, something Johnson knew was essential in a floor-fed system from his previous experience with group housing in the UK. In addition, two of the grower rooms were also converted to sows pens, giving a total capacity for 1120 sows from 30 days into gestation up to removal for farrowing. The remaining 6 grower rooms were used to construct a further 240 farrowing pens, while the original nursery rooms hold piglets ready for shipping. From weaning until 30 days, sows are housed in stalls in the existing breeding and gestation areas.

Experience with the group sow pens has been generally positive, but not without its teething problems, says unit manager Susan Armstrong. “Our biggest problem has been variation in the weight of feed dispensed, which has ranged from 7-12 lb per drop, making it difficult to feed accurately.” Gilts are penned separately and sows are grouped by body condition in order to feed more accurately, something that’s necessary when floor feeding. However, that makes it more difficult to remove sows for farrowing, says Armstrong. “We can’t remove all the sows at one time as we would if they were grouped strictly by breeding date,” she explains. Also, sow behaviour is rather aggressive with floor feeding, although no vulva biting has been noted so far. Scanning sows in the group has proved more difficult than when sows are in stalls. “We carry out the first scan when sows are in stalls in the implantation area, but we also like to do a second confirmation of pregnancy at 65 days,” Armstrong says.

Experience with the group sow pens has been generally positive, but not without its teething problems, says unit manager Susan Armstrong. “Our biggest problem has been variation in the weight of feed dispensed, which has ranged from 7-12 lb per drop, making it difficult to feed accurately.” Gilts are penned separately and sows are grouped by body condition in order to feed more accurately, something that’s necessary when floor feeding. However, that makes it more difficult to remove sows for farrowing, says Armstrong. “We can’t remove all the sows at one time as we would if they were grouped strictly by breeding date,” she explains. Also, sow behaviour is rather aggressive with floor feeding, although no vulva biting has been noted so far. Scanning sows in the group has proved more difficult than when sows are in stalls. “We carry out the first scan when sows are in stalls in the implantation area, but we also like to do a second confirmation of pregnancy at 65 days,” Armstrong says.

Farrowing the target of 85 sows per week started at the beginning of December and the goal is to wean 900 pigs per week at an age of 20-21 days. These are shipped to the USA with another 900 pigs from another barn to make up a full load of 1800. Big Sky has a contract in place for these pigs to be raised in wean-to-finish barns in Iowa, managed by South Central Management Services, but they retain ownership. Finished pigs will be marketed in the US Mid-West but, initially at least, not tied to a specific packer.

While the decision at the time was to finish pigs in the USA, they could just as easily be reared in low-cost contract finishing barns in Saskatchewan, says Richard Johnson. “It’s currently a lot more attractive to finish in the US, but that could change.” The main motivation for the unit remodelling was to improve return on capital, he stresses. “We will make more money doing this than operating a farrow to finish operation. We modelled a range of different scenarios for these barns with a range of feed prices and in every case the farrow to isowean option was the most profitable.”

Big Sky plans to convert more of the ex-CPV units, drawing on the experience of this first one, especially how the group housing works. “It may prove best to remove the partial pen divisions in the group pens, to allow for sows to move around freely while feeding.” Johnson feels. “Also, we may need to fine-tune space allowances and how we group sows according to age and condition.” So far, though, performance has been up to expectations, with the mainly gilt herd farrowing 11.9 born alive per litter.

In time, converting all the ten 600-sow barns would allow an increase in the company’s sow base of 12,000, but Johnson says that’s a long-term goal. “We do want to expand in order to reduce cost,” he says. “Also, having a lot of sows in group housing will give us additional marketing opportunities and could allow us to develop added value pork products.”

Photo captions:

- New_Sow_pens-1.jpg: Richard Johnson discusses the group sow pens with unit manager Susan Armstrong

2. Sows in group pens-1.jpg: Sows lie quietly in the converted finishing pens

Pigs Down Under

Posted in: Economics, Environment, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

High feed prices and low hog prices have led to a huge increase in sow slaughterings in Australia and there is a low level of confidence among producers, says production consultant John Riley. Meanwhile, imports of pork products soar, including those from Canada, putting even more pressure on producers.

The winter edition of the Western Hog Farmer summarizes the Canadian industry’s response to high feed costs, the weakness of the US dollar and unsatisfactory market returns.

The dismal picture in Canada is mirrored in the Australian industry. In the last month, one of the largest production units in Queensland that is owned by a Japanese company has been put on the market. If this 7,000 sow, farrow to finish business closes, there will be serious repercussions for the local feed mill and the two abattoirs in the state.

Another company to call it a day is the breeding company Hyfarm-JSR. They have sold their 600-sow high health nucleus unit to a Dutch family who recently settled in the state. In addition, the Hyfarm-JSR multiplication unit is now on the market with limited expressions of interest by prospective purchasers.

Ironically, the Dutch family were encouraged to settle in Australia by a state government in 2002 which promoted the financial benefits of investing in the pig industry in Queensland.

The Productivity Commission report that handed down its findings in December, determined that the unprofitability of the Australian industry was not due to imports from the USA, Denmark and Canada, but was due to high feed costs.

The Productivity Commission report that handed down its findings in December, determined that the unprofitability of the Australian industry was not due to imports from the USA, Denmark and Canada, but was due to high feed costs.

In parts of New South Wales and Queensland, harvesting of the sorghum crop is well advanced with record yields being recorded. Sorghum is a summer grain crop used in animal feeds. Normally the price is around $AU160 per tonne but this year the price is holding firm at around $AU$260 per tonne due to the high demand worldwide for wheat and barley. The usual seasonal reduction in average feed costs has not materialized so far in 2008.

During the last quarter of 2007, sow slaughtering was 49.5% higher than in the last quarter of 2006. The level of imports of processed pig meat during the 12 months ending December 2007 was 29% higher than in 2006 with imports from Canada totalling 43,415 tonnes shipped weight, an increase of 24.8% on the previous year. In the same period imports from the United States increased by 52%.

The lack of confidence in the industry has resulted in very little investment in housing systems that comply with the new welfare codes. The codes dictate that within ten years, housing of sows in stalls for more than four weeks during gestation will not be allowed.

A few producers in the east that have moved to group housing in gestation have adapted grower pens and introduced feeding of small groups.

In some instances in Western Australia sows have been housed in larger groups on deep litter in shelters and fed through traditional feeding stalls on a concrete pad in or adjacent to the shelter. The feeding stalls service more than one group of pigs on a rotation system. The main disadvantage of the system is the high labour required in moving sows.

There is only limited interest in electronic feeding systems. In the past Australia’s isolation in regard to after sales services has led to frustration and a few systems that were installed in the early 1990’s were subsequently removed. However, interest has been rekindled in recent months and two large-scale producers have installed Mannebeck systems in naturally ventilated slatted floor sheds.

In addition to high feed costs and poor market returns, producers in Queensland were shocked to read in March of their state government’s proposal to increase the cost of meeting the environmental legislation. The proposal, if implemented, will see a producer with 100 sows producing bacon pigs paying $52 per sow per year to government and a producer with 600 sows with progeny to bacon will pay about $9,800 per annum. The State government has decided on a policy of full cost recovery from potential polluters of the environment for the implementation and the policing of the legislation. Interestingly a local mining company selling gold worth $108 million will pay just $20,000 if the legislation is passed.

A further major change will dictate that multi-site operations will pay the fee on every site because multi site discounts will be withdrawn. Pig producers in Queensland are far from happy and more could well exit the industry in the next six months.

Photo caption:

Group sows-1 – Producers in Australia are moving towards group sow housing

News and Views – Safeway makes welfare moves

Posted in: Meat Quality, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

North America’s third largest grocery retailer, Safeway, has taken steps to improve animal welfare in its food purchasing decisions of pork and poultry. It will increase the amount of pork sourced from production systems that do not use gestation stalls by 5% per year over the next three years to a total of 15% in 2010.

The company also said it will favour the purchase of eggs from cage-free systems, stating that it will more than double the percentage of cage-free eggs it offers to over 6% of its total egg sales within two years.

The Humane Society of the United States (HSUS) applauded Safeway’s announcement. It has been in dialogue with the retailer since last November about improving its farm animal welfare standards.

New Product Showcase – Intervet introduces Circumvent™ PCV vaccine

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Intervet Canada Ltd. has announced the registration of Circumvent™ PCV vaccine for use in the prevention of PCV2 (Porcine Circovirus, type 2) infection in pigs.

Circumvent™ PCV, a proven efficacious vaccine against circovirus infection (PCVAD – Porcine Circovirus Associated Diseases), is now fully licensed in Canada and the US. This product has been available in limited quantities since spring 2006 through emergency use provisions to assist in the circovirus emerging disease crisis.

“Circumvent™ PCV has saved a lot of bacon”, said Dr. Jorgen Jorgensen, General Manager of Intervet Canada. “Two years ago we received the first supply of this product to be tested in Canada. It wasn’t long before we witnessed significant results. Mortality rates of 40 to 50% were reduced dramatically down to low single digits.”

“Veterinarians and producers are also seeing secondary benefits when vaccinating with Circumvent™ PCV,” said Dr. Jorgensen. “Along with the dramatic decrease in mortality, producers are also experiencing better growth rates, heavier pigs and healthier herds. The use of antibiotics has been reported to have dropped, even in the presence of PRRS and feed gain has improved, demonstrating that the investment of vaccination is returned many times,” said Dr. Jorgensen.

Circumvent™ PCV is registered for use in healthy swine, three weeks of age or older, as an aid in the prevention of viremia and virus shedding caused by Porcine Circovirus, type 2.

For additional product, technical or order information please contact your Intervet Technical Sales Representative, log on to www.intervet.ca or call 1-800-268-4257.

Manitoba Swine Seminar – Segregating sows by parity improves performance

Posted in: Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Segregating gilts and sows into sub-populations based on parity and providing different nutritional regimes can increase the number of pigs born per litter and per sow lifetime, says Dr. Dean Boyd, of the Hanor Company, Franklin, Kentucky. This is because the amount and type of nutrients required by young, immature sows (1-2 litters and older females (>5 litters) is very different, he told delegates at the Manitoba Swine Seminar. Furthermore, such an approach compliments health and reproductive considerations, he says.

The fist litter female is especially vulnerable to body protein loss during lactation, explains Boyd. “The foremost consideration is to formulate and feed to conserve body protein loss, since there is a direct effect of this on wean to estrus (WEI) interval and second litter size,” he says. “For example, a 4kg body protein loss during first lactation is sufficient to reduce second litter size by 0.75 pigs, whereas, in contrast, limiting protein loss to less than 2 kg can result in a second litter size 1.0 higher than the first.” WEI increases in proportion to body protein loss and it is not uncommon for it to be extended by up to 10 days for gilts that have raised a large litter, milked well and suffered too much protein loss. “Unfortunately, this is sometimes interpreted as ‘reproductive failure’ and may result in early culling from the herd,” notes Boyd.

Total pigs born and born alive increase until the third litter, are then constant until about litter 5 or 6 and, thereafter, a progressive decline is observed. Boyd says this parity-related decline seems premature from a reproductive perspective. “The lost opportunity is probably in the order of 1.8 to 3.3 pigs per sow lifetime, depending on whether productive life is 8 or 10 litters,” he believes. “We hypothesize that this is due in part to the progressive decline in micro-nutrient profile as the sow ages.”

Micro-nutrient deficiency in older sows

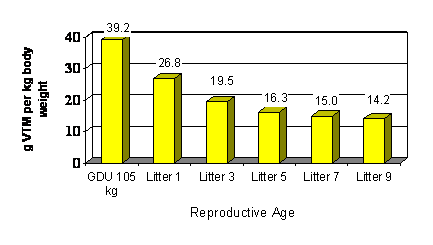

Micro-nutrients consist of Vitamins and Trace Minerals (VTM) and represent 0.12-0.15% of the diet but about 50% of the nutrients. In theory, micro-nutrients are formulated in diets at levels that prevent deficiency and include a margin of safety. However, says Boyd, there is a steady decline in the “safety margin” with increasing reproductive age. The reduction in body mineral levels that has been observed is most likely because pregnancy feed intake is held about constant (once body condition has been restored) across all parities, in order to limit growth. However, body weight progressively increases with reproductive age, Boyd points out. “This ‘constant’ feed policy is appropriate for protein and energy needs, however, it probably does not work for VTM because the amount that is required to support normal tissue metabolism increases with the increase in tissue mass,” he says. This results in a marked decline in the grams of VTM/kg body weight with increasing parity (Figure 1). “The problem is that this occurs with each pregnancy and, to a lesser extent, in lactation,” Boyd explains. “Thus, the older, heavier sow is placed at increasing nutritional risk, reproductively and immunologically.”

Figure 1: Example calculation of declining Vitamin – Trace mineral intake

with advancing reproductive age, g VTM / kg body weight

(Calculated by Boyd and Hedges, 2004, using PIC USA 2002 ADFI x

sow weight by parity, assuming 0.149% dietary VTM )

The hypothesis that an age-related decline in litter size might be nutrition related was tested in the mature sow (parities 3-10) sections of two Hanor farms. In each farm, parity segregation is practiced by designating one section for sows of parity 3 or more. In the trial, control sows received 0.15% VTM as usual, whereas the test diets for older sows were designed to provide the same VTM per kg bodyweight for a P-7 female as would be provided to a P-3 sow. The annual cost of this increase was approximately $1.69 per sow, compared to the control diets. Evaluation of herd data showed that the diets equalized for VTM did, in fact, improve performance. “Litter size weaned was improved for sows in parities 4 to 10 by an average of 0.6 pigs per litter of 1.44 pigs/sow/year,” notes Boyd. “However, sow viability was not significantly improved during the term of this study”.

The concept of organizing the sow farm in order to nutritionally manage younger and older females differently, was originally demonstrated in the Hanor system by dividing the herd into three sub-populations, however, this has now been reduced to two. This nutrition-specific approach has been shown to lead to increased lifetime pig output and reduced risk to sow viability with no increase in feed cost per weaned pig. “For young females, the expected outcome is to improve lifetime pig output by producing a large first litter and then to manage her in a way that does not compromise second litter size,” say Boyd. “Once P-1 females are successfully re-bred and managed to 30 days of gestation, then the need for specialized ‘young sow’ nutrition probably ends.” However, he notes, there may be health-based reasons for also keeping younger sows in this sub-population.

Manitoba Swine Seminar – British researcher suggests high fibre feeds for sows

Posted in: Environment, Production, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

With the cost of feed ingredients continuing to increase, hog producers may want to consider some non-conventional and less costly sources of animal nutrition, suggests Professor Peter Brooks of the University of Plymouth. Sources include silage materials (grass, maize, corn cobs), food industry by-products (from the production of bio-ethanol,

for example) and root crops (fodder beets and potatoes).

Peter Brooks, head of the School of Biological Sciences at the British university and a professor of animal production, was in Winnipeg on January 30, to speak to Manitoba hog producers attending Manitoba Swine Seminar 2008 about the importance of fibre in sow diets. He noted that researchers over the past 20-25 years have come to recognize that recommended feed intake levels for gestating sows are considerably less than the amount of feed they actually require.

“The stereotypical behaviour often observed in confined gilts was generally put down to boredom and frustration,” he noted. “But a study in 1987 (by Appleby and Lawrence) demonstrated that an increase in a sow’s feed intake from 1.25 to 4 kg a day almost completely eliminated the behaviour.” He added that incorporating fibre in diets to increase bulk, without changing the dietary energy supply, resulted in at least a doubling of eating time, a 20% reduction in feeding rate and a decrease in restlessness and aggression. “It would appear that foraging behaviour is an intrinsic drive in pigs and that bulkier diets that take longer to consume help to satisfy this need,” he said.

Brooks reported that other studies show that providing sows with straw bedding also reduces the stereotypical behaviour. Although the use of straw is widespread in the UK, he noted, elsewhere in Europe producers use slatted floors, which are geared for liquid manure systems rather than solid manure. In Northern Ireland, Brooks reported, producers have tried putting straw in racks for the sows to eat. That hasn’t been that successful because too many of the sows spend time exploring the racks instead of

eating the straw.

Offering grass rather than straw in the racks seems to be more appealing to the sows. Brooks cited studies that show that sows will consume an average 2kg of grass silage a day and that the grass is easily digestible. He reported that some commercial units have successfully tried grass and maize silage and corn cob mix in conjunction with electronic sow feeders.

Other potential fibre sources for sows that Brooks identified were wheat and rice bran, malt culms, oat husks, soya bran hulls, sugar beet pulp and citrus pulp. There have been some experiments in Europe with chicory pulp, too. Studies indicate that feeding sows sugar beet pulp and citrus pulp produce the best results.

Brooks added that in Europe as many as 30% of sows are being fed liquid diets which makes the animals more restful. That is because the solid fraction of the diet becomes hydrated more quickly, altering the viscosity and rate of gut transit of the diet. High fibre diets, in particular those that include sugar beet pulp, reduced water consumption by sows with an accompanying reduction in urinary output.

In concluding, Brooks observed that higher prices for traditional feed ingredients combined with a greater understanding of the nutritional needs of sows and the growing public demand for more humane housing solutions means that producers have to rethink how they house, feed and manage sows.

Manitoba Swine Seminar – PRRS continues to be major health challenge, says Minnesota vet.

Posted in: Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Despite good success in controlling and reducing PRRS in North America, the virus continues to be a leading cause of illness among sows, says Dr. Tim Loula. “PRRS has been the major health challenge in the industry since the 1980s,” said Loula, a veterinarian working out in the Swine Vet Center in St. Peter, Minnesota.

Loula was in Winnipeg on January 30 to address producers attending Manitoba Swine Seminar 2008. This past winter, he reported, a large percentage of the American

Midwest was infected with PRRS and there was an outbreak in China in January. He noted that outbreaks are worse in winter. Among the effects of the disease, Loula listed lower litter size, lower farrowing rate, lower average daily gain, increased feed conversion, increased cost of medications and vaccinations, increased variation, decreased number of full value market hogs and higher mortality rates.

Loula described the creation of a North American PRRS Eradication Task Force that was initiated at the AASV board of directors meeting in Kansas City in 2006. The Task Force’s goal is the complete eradication of PRRS. Members, Loula said, have been starting local task forces in their regions bringing together producers, production systems, vets, industry partners and researchers to eliminate the disease region by region. He reported that such task forces have already been established in Ontario, North Carolina and Minnesota. Three counties in Minnesota have eradicated PRRS in their area.

“The first step is to map out where the pigs and the viruses are so that we can track where they are going,” Loula said. He discussed some current methods of eliminating the disease in specific herds. One way is to depopulate and then repopulate the site. By moving the entire herd out of the barn, the producer is able to clean and disinfect the entire site. The herd is brought back in after everything has dried and the process takes about a week. Follow-up studies, Loula reported, show that 49% of farms are still clear after 120 weeks and 39% after 150 weeks.

Herd closure is another method of controlling or eliminating PRRS by stopping the introduction of replacement animals to the sow herd for an extended period of time. Those farms that have kept out replacement sows for more than 200 days have generally been successful. This method allows the herd to develop a strong immunity to the virus. New sows can be brought in 30 days after the last clinical signs of the disease.

Producers can also try a direct virus exposure using serum. Of more than 150,000 sows thus treated, Loula said, there were only two bad experiences. A test and removal approach, Loula noted, is not in common use and works best alongside a second type of stabilization program.

Loula spoke of biosecurity measures intended to keep PRRS at bay in the first place. He suggested filters to keep insects out of the barns and having visitors remove their shoes.

He also noted that vaccines are also available for some strains. “Hog producers need to become knowledgeable about epidemiology, sanitation and biosecurity,” Loula said. “That will benefit you long after the herd is free of the disease.”