Literature Review and Needs Assessment of Housing Systems for Gestating Sows in Group Pens with Individual Feeding

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre, Uncategorized by admin on August 9, 2011 | No Comments

In the U.S., the public has expressed concern over the use of sow gestation stalls via ballot measures in a number of states. Likewise, large companies such as Smithfield Foods and Canada’s Maple Leaf Foods are voluntarily restricting the use of gestation stalls by 2017. Gestation stalls have already been banned in the U.K. since 1999, with the rest of Europe phasing them out by 2013, and Australia by 2017. On the surface, it may appear that this is a step towards improving the welfare of gestating sows, however, animal welfare is a multi-faceted concept and scientific data is needed to assess all components. This article describes some of the literature that assesses the different housing systems for gestating sows.

Effects of Temperament and Floor Space Allowance on Sows at Grouping

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre, Uncategorized by admin on | No Comments

Many North American producers are anticipating a change to group housing for sows. The overall purpose of this study was to determine how to reduce the stress of mixing sows by altering space allowance, and social groups. We also studied how space can influence behaviour and aggression within a goup. The largest space requirement occurred between midnight and 8am when the highest percentage of sows were lying laterally. From a purely physical perspective the sows would require 1.51m2/sow, however this does not account for any movement or interactions between individuals. When sows were initially grouped, they showed a higher occurrence of injury scores (P<0.001) and a greater number of fights (P<0.001) compared to the stable groups (3 weeks post-mixing). Most fi ghting and injuries occurred within 24 hours of mixing. There was not a significant difference between either injury score and number of fights with the different space allowances. Passive/shy sows appeared to show a reduced stress response compared with active/bold sows.

Yeast culture supplement during nursing and transport affects immunity and intestinal microbial ecology of weanling pigs

Posted in: Production, Uncategorized by admin on August 4, 2011 | No Comments

The objectives of this study were to determine the influence of a Saccharomyces cerevisiae fermentation product on innate immunity and intestinal microbial ecology after weaning and transport stress. In a randomized complete block design, before weaning and in a split-plot analysis of a 2 × 2 factorial arrangement of yeast culture (YY) and transport (TT) after weaning, 3-d-old pigs (n = 108) were randomly assigned within litter (block) to either a control (NY, milk only) or yeast culture diet (YY; delivered in milk to provide 0.1 g of yeast culture product/kg of BW) from d 4 to 21. At weaning (d 21), randomly, one-half of the NY and YY pigs were assigned to a 6-h transport (NY-TT and YY-TT) before being moved to nursery housing, and the other one-half were moved directly to nursery housing (NY-NT and YY-NT, where NT is no transport). The yeast treatment was a 0.2% S. cerevisiae fermentation product and the control treatment was a 0.2% grain blank in feed for 2 wk. On d 1 before transport and on d 1, 4, 7, and 14 after transport, blood was collected for leukocyte assays, and mesenteric lymph node, jejunal, and ileal tissue, and jejunal, ileal, and cecal contents were collected for Toll-like receptor expression (TLR); enumeration of Escherichia coli, total coliforms, and lactobacilli; detection of Salmonella; and microbial analysis. After weaning, a yeast × transport interaction for ADG was seen. Transport affected ADFI after weaning. Yeast treatment decreased hematocrit. A yeast × transport interaction was found for counts of white blood cells and neutrophils and for the neutrophil-tolymphocyte ratio. Monocyte counts revealed a transport effect. Interactions of yeast × transport and yeast × transport × day for TLR2 and yeast × transport for TLR4 expression in the mesenteric lymph node were detected. Day affected lactobacilli, total coliform, and E. coli counts. More pigs were positive for Salmonella on d 7 and 14 than on d 4, and more YY-TT pigs were positive on d 4. The number of bands for microbial amplicons in the ileum was greater for pigs in the control treatment than in the yeast treatment on d 0, and this number tended to decrease between d 1 and 14 for all pigs. Similarity coefficients for jejunal contents were greater for pigs fed NY than for those fed YY, but pigs fed YY had greater similarity coefficients for ileal and cecal contents. The number of yeast × transport × day interactions demonstrates the complexity of the stress and dietary relationship.

For more information the full article can be found at http://jas.fass.org/

Endocrine response of gilts to various common stressors: A comparison of indicators and methods of analysis

Posted in: Production, Uncategorized by admin on July 25, 2011 | No Comments

The first aim of the present study was to determine whether various common events encountered by pigs in commercial farms or experimental units induce activation of the sympathetic and hypothalamo-pituitary adrenal (HPA) axes. The second aim was to compare the efficiency of various indicators and methods of analysis to detect the occurrence of a stress reaction. Responses to two blood sampling methods, immobilization by snaring, brief electric shocks, loud noise, ear tagging, tattooing, biopsy, pen relocation or delayed feeding time have been evaluated. Series of blood and saliva samplings (from 10 min before to 120 min after stressor application) were collected for each stressor on a total of 8 catheterized sows. Plasma glucose, lactate, cortisol and ACTH levels as well as salivary cortisol were measured. Acute increases of cortisol or ACTH (at least at time points+5 or+15 min) were observed for intense noise, electric shocks, ear tagging, tattooing, biopsy, cava blood sampling, snaring and pen relocation. Snaring, relocation and vena cava blood sampling generated longer stress responses whereas delayed meal and tail blood sampling had no influence. Plasma lactate was also significantly increased in several time-points after stressor application contrarily to plasma glucose. Comparison of successive time points with the starting basal level and comparison with the control group were more sensitive methods to detect a stress response to moderate stressors like electric shocks and tattooing, than comparing the area under the curve. These data confirmed that salivary cortisol is a good indicator to measure the HPA response to a stressor, provided that post-treatment levels can be compared with pre-treatment levels.

For more information the full article can be found at http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/00319384

Aggression in replacement grower and finisher gilts fed a short-term high tryptophan diet and the effect of long-term human–animal interaction

Posted in: Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Aggression can be a major problem for swine production as it negatively impacts the pigs’ health and welfare. Increasing tryptophan (TRP) intake to raise brain serotonin (5-HT)—key for aggression control, and long-term positive social handling can reduce stress in pigs. Objective was to feed a short-term high-TRP diet to grower (3 months) and finisher (6 months) maternal gilts that were either socially handled or not and measure their behavioural activity and aggressiveness. Eight pens of six unrelated gilts were split into two blocks balanced for litter, social handling (non- vs. handled) and dietary treatment (control vs. high-TRP). Social-handling was applied three times per week, from day 45 until 6 months of age. At 3 months, two handled and two non-handled pens were assigned to control while the other four pens were assigned to the high-TRP diet fed ad libitum for 7 days. At 6 months of age, pen assignment to dietary treatments was swapped. Body weights and blood were taken at the start and at the end. Blood samples were analyzed for TRP and 5-HT concentrations using high pressure liquid chromatography. Behaviour was recorded from days 1 to 5 and scan-sampling used to determine time-budget behaviours and postures in a 12-h period each day. Aggression evaluation in the home pen focused on counts of agonistic interactions, bites and head-knocks per interaction during three, 30-min intervals (08:00, 12:00, and 16:00 h) from days 1 to 5. Resident–intruder test was carried out for a maximum of 300s at days 6 and 7 to measure aggressiveness, predicted by the latency to the first attack and attack outcomes. A 2×2 factorial arrangement of dietary treatment and social handling within age was analyzed by repeated measures of mixed models and Tukey adjustments. The TRP-added diet raised blood TRP concentration of 3- and 6-month-old gilts by 180.7% and 85.2% respectively, reduced behavioural activity and time spent standing, while increasing lying behaviour, mostly in grower gilts. High-TRP diet reduced the number of agonistic interactions, and aggressiveness in 3-month old gilts, which took longer to attack the intruder pig, and displayed fewer attacks on the first day of testing. Long-term positive social handling improved growth performance and had a slight effect on behaviour (P< 0.05). Provision of enhanced TRP diet reduced behavioural activity and aggressiveness of grower gilts, and these results are likelymediated by activation of brain serotonergic system. Short-term high-TRP dietary supplementation may be used to reduce aggression at mixing in young pigs.

For more information the full article can be found at http://journals.elsevierhealth.com/periodicals/applan/issues

Incorrect temperatures found in 36% of semen storage units

Posted in: Uncategorized by admin on July 14, 2011 | No Comments

A recently published study of semen storage temperatures carried out in Ontario showed that inappropriate temperatures were recorded in 36% of on-farm storage units. The authors, Drs. Beth Young, Cate Dewey and Robert Friendship, noted that producer errors, including adding warm semen to the unit, poor unit maintenance, and poor temperature control, were the most frequent causes of incorrect temperatures.

“Semen is cooled during storage to decrease the metabolic rate of the sperm,” explained the authors. “When semen is stored at temperatures of more than 20°C, sperm maintain a high metabolic rate with rapid energy consumption and by-product production, resulting in a short shelf life. Temperature fluctuations can also impact stored semen quality, and it has been suggested that for each 2°C to 3°C fluctuation in semen temperature, the shelf life of that semen is decreased by one day, they noted. Because boar sperm are particularly temperature sensitive, appropriate on-farm semen storage is a critical factor in achieving good AI results.”

For the survey, a sample of 27 Ontario swine farms was visited and on each farm, an air-temperature-logging device, set to record air temperature at 1-minute intervals, was placed in the farm’s semen storage unit. A log sheet was taped to each storage unit, and producers were asked to record the date, time, and reason each time the storage unit door was opened. The type of storage unit (refrigerator-type or cooler-type) was also recorded.

Storage unit temperatures that fell outside the temperature range of 15°C to 20°C for ≥ 40 minutes were considered unacceptable. Storage-unit temperatures that fluctuated by ≥ 2°C for ≥ 40 minutes were also considered unacceptable.

In one herd, semen was stored in two separate storage units, so temperature data was collected from a total of 28 storage units. The average number of times the storage units were opened was 2.8 times per day, with the minimum zero times per day and the maximum eight times per day. The most commonly reported reason was to remove semen doses for breeding (Table 1).

Table 1: Reasons recorded by producers for opening their semen storage units, reported as a percent of 166 door-opening events*

| Recorded reason for opening storage unit | Percent |

| Removing semen doses for breeding | 56.0 |

| Returning unused semen after breeding | 19.3 |

| Loading fresh semen into storage unit | 6.0 |

| Turning semen doses | 6.0 |

| Adding frozen gel packs to storage unit | 4.2 |

| Removing doses for semen evaluation | 2.4 |

| Checking thermometer in storage unit | 1.8 |

| Removing-replacing drug bottles in storage unit | 1.8 |

| Counting semen doses | 1.2 |

| Returning gel packs after breeding | 1.2 |

* Results reported for 26 storage units on Ontario farms visited between May and October, 2004. Door-opening events were recorded for 72 hours.

Unacceptable semen storage temperatures were recorded in 10 of 28 (36%) of the storage units examined. Nine of these 10 storage-unit temperatures were considered unacceptable because temperatures were outside the 15°C to 20°C range for ≥ 40 minutes. In eight of the nine units in which temperatures fell outside the 15°C to 20°C range, temperature fluctuations of > 2°C were also recorded. The type of storage unit used was not associated with inappropriate semen storage temperature. However, a polystyrene picnic cooler used by one farm performed very poorly.

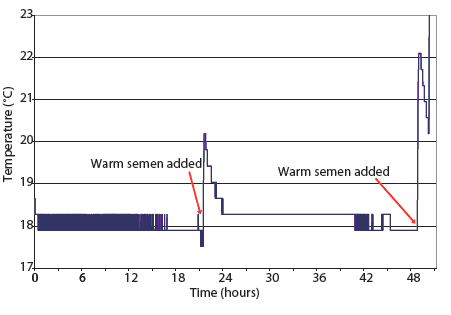

In seven of the 10 problem storage units (70%), the unacceptable temperatures appeared to have been triggered by specific events recorded by the producers. In three cases, unacceptably high temperatures occurred when warm, fresh semen doses were put into the storage unit (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Temperatures recorded by an air-temperature-logging device at 1-minute intervals in a semen storage unit in which temperatures exceeded 20°C and fluctuated by > 2°C when warm semen was placed inside the unit.

Poor maintenance of the storage unit was the cause of unacceptable storage temperatures in two cases. In one, the storage-unit door did not close properly and occasionally opened unexpectedly. This happened once during the temperature-recording period. The temperature in the storage unit fell to the air temperature of the barn (13°C to 14°C) and the temperature remained low for approximately 10 hours until the door was closed. In the other case of poor maintenance, a storage unit with a frayed electrical cord failed while the temperature logger was in place. In less than 2 hours, the temperature in the storage unit rose to 22.5°C. The problem was noticed and ice packs were added to the storage unit, which caused the temperature to drop rapidly to 8.6°C. Approximately 4 hours after the storage unit first failed, a new electrical cord was installed and the temperature in the storage unit stabilized within the appropriate range.

In two instances, poor temperature regulation of the unit caused unacceptable storage temperatures. In one case, the thermostat was set too high and the storage unit consistently maintained a temperature > 23°C. In the other case, a polystyrene picnic cooler with ice packs was used as a semen storage unit. Each time an ice pack was added, large temperature fluctuations occurred (up to 4°C), and the temperature fell below 15°C for approximately half of the temperature-recording period.

In this study, more problem storage units produced temperatures that were too cool than temperatures that were too warm. Boar sperm is extremely sensitive to cold shock, which is one reason the use of frozen boar semen is not a practical alternative for the swine industry.

Nine of the 10 problem units experienced temperature fluctuations of > 2°C. Variation in storage temperature forces sperm to re-adjust their metabolic activity in order to adapt to changes in their thermal environment. This depletes nutrients and buffer in the extender and diminishes semen quality.

Most problems with storage temperature in this study were directly attributable to the actions of the producers. This suggests that more emphasis on producer education in proper storage-unit management and maintenance is needed, say the authors of the study.

Most problems with storage temperature in this study were directly attributable to the actions of the producers. This suggests that more emphasis on producer education in proper storage-unit management and maintenance is needed, say the authors of the study.

Thirty percent of the unacceptable storage temperatures were attributable to adding still-warm semen to the storage unit. If there is cooled semen in the storage unit when the warm semen is placed inside, the higher air temperature caused by this action may have a negative impact on the quality of the cooled semen. Some means to avoid placing warm semen in the storage unit include allowing the semen to cool to below 20°C in an area of the barn cooled by a fan or air conditioner, or to have two separate units, one for cooling semen and one for storing semen once it is cooled, suggest the authors.

Because poor maintenance was identified as a cause of unacceptable storage temperatures, producers should be encouraged to regularly maintain their storage units. Storage units should be routinely inspected and damaged parts should be repaired or replaced. Units should also be cleaned regularly to prevent dust from building up around the air circulation system, which may cause inefficient operation or overheating. Daily temperature monitoring should also be a part of routine storage-unit maintenance. Simple high-low thermometers are an inexpensive, easy and effective method for producers to monitor temperatures inside their semen storage units, concludes the report.

Reference: Young B, Dewey CE, Friendship RM. Prevalence and causes of inappropriate temperatures in on-farm semen storage units in Ontario. J Swine Health Prod. 2008;16(2):92–95.

Take home messages:

|

Photo: Semen fridge-1 – A study carried out in Ontario showed that inappropriate temperatures were recorded in 36% of on-farm storage units

Eye on Research – The effect of space and group size on finisher performance

Posted in: Prairie Swine Centre, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

With the current shift in the industry toward housing pigs in groups of 100 to 1,000 per pen, questions have been raised as to whether pigs can perform as well in large groups as they do in small ones. Recent work at the Prairie Swine Centre examined how housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations affects production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables. The studies looked at the effects of small (18 pigs) vs. large (108 pigs) group sizes provided with 0.52 m2/ pig (crowded) or 0.78 m2/pig (uncrowded) of space on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Pigs in the crowded groups spent less time eating over the eight-week study than did pigs in non-crowded groups. However, average daily feed intake (ADFI) did not differ between treatments. Overall, ADG of large-group pigs was 1.035 kg/day, whereas small group pigs gained 1.073 kg/day. Average daily gain differences between the group sizes were most evident during the first two weeks of the study.

The investigation found that, over the entire study, large groups were less efficient than small groups. Although large-group pigs had poorer scores for lameness and leg scores throughout the eight-week period, morbidity levels did not differ between the group sizes. Minimal changes in postural behaviour and feeding patterns were noted in large groups.

An interaction of group size and space allowance for lameness indicated that pigs housed in large groups at restricted space allowances were more susceptible to lameness. Although some behavioural variables, such as lying postures, suggested that pigs in large groups were able to use space more efficiently, overall productivity and health variables indicate that pigs in large and small groups were similarly affected by the crowding imposed in this study.

The trial indicated no difference in the response to crowding by pigs in large and small groups. Little support was found for reducing space allowances for pigs in large groups.

WHJ comment: There is no doubt that the North American pork industry has enthusiastically embraced large group grow-finish systems in order to obtain the benefits of auto-sorting equipment, which leads to more optimal market weights and saves labour. However, little is known about the implications for pig performance and welfare. This study suggests that space allowance has a bigger effect on growth than group size, although ADG was better for the small groups. The suggestion that pigs in large groups make better use of space and therefore need less space per pig seems to be disproved by this work. Even though there are disadvantages in both performance and some measures of welfare, the trend towards large groups is likely to continue due to the magnitude of the benefits.

Reference: B. R. Street and H. W. Gonyou. – Effects of housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

J. Anim Sci. 2008. 86:982-991. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0449

Brits roll out the charm offensive …and it’s working!

Posted in: Uncategorized by admin on | No Comments

UK producers have been hit with rocketing raw material prices just like the rest of the world and are currently losing $40 per slaughter pig. Some shrewd and farsighted pig farmers bought forward last summer, but many got caught out. Now even producers who grow their own grain are having to buy in as last harvest’s stocks have been used up. Some operators have used the current crisis to depopulate and re stock, whilst many contract finishers have opted to leave their barns empty. Having said that, high raw material prices are not a one-year wonder and for the UK industry to survive the producer must get a decent price for his pigs – $2.80 per kg. British farmers tended to look down their noses at their counterparts across the English Channel who over the years have staged noisy demonstrations to draw attention to low prices, yet who would have believed that a few years ago, during the last pig crisis, Yorkshire pig farmers, immaculately dressed in a flannel shirt, tie, sports jacket and smartly tailored trousers could be found manning picket lines at many of the big supermarkets’ massive distribution centres, causing huge disruption to these operations . A small group of hard headed Yorkshire producers were fed up with falling UK pig prices and the sight of supermarket shelves full of imported pork and bacon, so they set up the British Pig Industry Support Group (BPISG), a somewhat clandestine group of producers, their employees plus allied industry staff. These picketing operations were well planned, usually taking place on Thursday nights as these centres were working flat out getting products out for anticipated big weekend sales. One such operation caused massive disruption to a huge distribution centre near Doncaster resulting in a complete shut down by 2am the following morning, losing that company thousands of dollars. As the weary protesters drove home, they passed a long line of 90 loaded refrigerated semis, all stood stationary, backed up for 3km and which wouldn’t be unloaded until the day shift came into work. That’s what you call Pig Farmer Power!

About 18 months ago, when prices were again low, the “nightriders” went out again. Previously any brushes with the police had been good-natured, but on this occasion the police outnumbered the pickets, turned up with dogs and threatened arrest for trespass. Hence Plan B had to be devised.

About 18 months ago, when prices were again low, the “nightriders” went out again. Previously any brushes with the police had been good-natured, but on this occasion the police outnumbered the pickets, turned up with dogs and threatened arrest for trespass. Hence Plan B had to be devised.

Traceability and independently audited quality assurance have been part and parcel of UK pigs for many years. All pork, bacon, ham and sausages produced under this scheme carry an easily identifiable distinctive colourful logo incorporating a Union flag, the British Meat Quality Standard Mark (QSM) on the pack. The British consumer has always been concerned about welfare and surveys carried out 15 years ago indicated that consumers didn’t like sows in stalls and appreciated that loose systems increased production costs, but wouldn’t pay more for the end product. This has changed over the years. Now British producers “play the welfare card” to justify the higher cost of the UK product versus cheaper imports and, according to a recent survey, 78% of people polled were prepared to pay a little more to cover rising production costs and support British producers. Only 9% of those surveyed thought that farmers were paid a fair price by British retailers. This COOL initiative has worked very well for the British pig farmer, but our circumstances are somewhat different to those existing right now in Canada.

The Meat and Livestock Commission (MLC) is a Government body set up many years ago to oversee the UK pig industry with regard to research projects and promoting livestock in general. Many UK pig producers felt that the MLC was not responsive enough with regard to industry needs and so the British Pig Executive (BPEX) was set up a few years ago. The BPEX board is made up of 7 leading English producers along with 3 key players in the processing trade. BPEX operates with maximum autonomy within MLC’s statutory responsibilities. An example of this is that in the past MLC might have decided to carry out research that in the view of pig farmers was too far removed from the “ coal face”. Now research topics are agreed by BPEX and implemented by MLC.

The profile of the British industry has been significantly raised of late and a lot of this is due to the hard work of producer Stewart Houston. Stewart plays an extremely pivotal role in the industry being an MLC commissioner and chairman of BPEX. Significantly Stewart is currently NPA executive director as well as NPA chairman. Stewart is on first name terms with key Ministers in the Government and so can put pressure on key politicians at very short notice, plus he has good working relationships with the big supermarkets. Consequently when raw materials shot up in price last summer NPA/ BPEX were quick off the mark explaining to the supermarkets that this was a worldwide problem and that they would not be able to source cheap pigmeat from abroad, as has happened too many times in the past, and that they needed to be aware that UK producers were losing $40 per pig. If retail prices didn’t lift then it would mean the demise of the UK pig industry. Pig producers regularly monitor the supermarkets for the amounts and type of imported pork and bacon being sold and this is displayed in the form of a league table. This invaluable data can then be used by industry leaders to put pressure on certain supermarkets to sell more British product. Good communications are vital in any sector. Pig farming is a very isolated business. This has been recognized here and excellent links have been established via the press, websites and SMS messaging. PIGWORLD is now the sole surviving pig magazine in the UK – not long ago we had three. It devotes many pages to NPA activities each month and editor Digby Scott also runs the NPA website. This site is updated daily plus a forum page displays comments and queries from anyone in the industry. Hence the UK industry is “very light on its feet “ and can respond to any crisis or development literally within hours, never mind days. We also musn’t forget the ladies. Ladies In Pigs (LIPS) do a sterling job touring the country promoting the industry at shows and backing up other demonstrations. The smell of cooking bacon is irresistible – even to vegetarians, some of whom think bacon isn’t meat (don’t dispel that myth though!) and these ladies, all unpaid volunteers, do a great job dishing out bacon sandwiches from their mobile kitchen across the length and breadth of the kingdom as and when required.

Part of plan B still involves demonstrating, but rather less confrontationally than at the turn of the century. The Institute of Grocery Distribution holds its AGM each year in October and pig farmers used this meeting as an opportunity to ram home the current crisis. Seventy producers braved the driving rain to demonstrate outside London’s Royal Lancaster Hotel with the message that if the UK industry becomes decimated then in 12 month’s time pork, bacon, ham and sausage prices will have gone sky high. A masterstroke was the presence of LIPS serving delegates with delicious bacon sandwiches as they arrived for their meeting. October is also the time of year when the industry celebrates British Sausage Week, which has now been running for 10 years. A TV celebrity is crowned “King of Sizzle” and tours the country in a bid to find Britain’s Best Banger. Organized by the British Sausage Appreciation Society, British Sausage Week celebrates the taste, quality and variety of the sausage of which there some 400 named varieties in Britain alone. Sausages are now a quality meat dish made of 90% pork, not rusk and bread as used to be the case, and British Sausage Week has undoubtedly raised the profile of the humble “banger “ over the last 10 years.

The Pig – O – Meter appeared on the BPEX website. This was an ingenious idea and shows vividly how much money the industry was losing minute by the minute, hour-by-hour and day-by-day. Another winner has been the “Pigs are worth it” website. www.pigsareworthit.co.uk/epetition.html This advert states that the industry is losing $12 every second. It shows a picture of a disappearing pig and pig farmer and then an empty pen with a caption “Save our bacon, before it’s too late” and urges viewers to register and log on line to show their support for the industry.

BPEX has spent $5 million (which included $1.6million from the government for post –FMD recovery) on the campaign to get a fairer return for UK pig farmers, which has included a series of high profile consumer adverts, which started last September, in national newspapers, magazines and supplements. Many of the leading TV cooks have also come on board, supporting retail price increases to save the industry. Incidentally, pig farmers pay a levy for pig meat promotion of $1.70 per pig, although because of the current crisis producers are getting a 12-month levy reduction of 20cents per pig from April 1. Processors contribute 40 cents per pig.

Pig farmers were encouraged to write to their local newspapers and contact their local radio and TV stations to promote awareness of the industry’s plight. Coaching in presentational skills was given to individuals so that the message came across in a professional way.

Another brilliant NPA idea was to get a nationwide group of pig farmers, wives and family together in an EMI recording studio to make a recording of “Stand by Your Ham”, a spin off of the 1968 Tammy Wynette classic “Stand by your Man”. The recording was released just before the “Pigs are worth it! Rally”, which took place on March 4 outside Downing Street, home to UK Prime Minister Gordon Brown. A petition containing over 13,000 names was handed in to the Prime Minister’s residence, 10 Downing St. Farmers were also joined by “Winnie The Pig”, veteran of the industry’s 3-month protest in front of the Houses of Parliament in the year 2000. (Winnie was so called because her pen was literally under the famous statue of Sir Winston Churchill, in Parliament Square). I was proud to help out in 2000 and recount the tale whereby I wheeled a barrow of pig manure up Whitehall at 7.30am, to be used to fertilize PM Tony Blair’s rose trees. The policemen on duty thought otherwise and I had to wheel it all back again!

The March 4 demo was a huge success, with over 1000 farmers turning out from all over the country. Local co-ordinators worked their socks off sending countless SMS messages to keep farmers updated regarding bus departure times and the like. The press coverage was simply amazing. I left home at 6am and “Stand by Your Ham “ was played constantly on national radio, all morning. The video clip also featured on national Breakfast TV and at other times and many foreign TV crews covered the event. The rally featured in 9 national newspapers, 17 regionals and on countless websites. In fact, Ontario Pork wants to use “Stand by Your Ham “ at their next AGM!

Farmers met their MPs after the rally and many MPs had their picture taken with Winnie, amongst them former Tory Agriculture Minister John Gummer. Government support has come from the appropriately named MP Richard Bacon who has tabled a cross party Early Day Motion which will call for the Government’s support to stop the disappearance of British pig farming.

Supermarkets have raised pigmeat prices but little, if any, of this increase has flowed down the supply chain to the producer.

The industry is not resting on its laurels. Using the March 4 rally as a springboard, a special trailer carrying pigs is embarking on a nationwide tour. The pigs will be parked in town centres with placard-waving farmers putting across the message that the industry is in dire straights and singing – of course – “Stand by Your Ham”!

It’s absolutely amazing what a small nucleus of determined individuals, working night and day, have achieved over the last few months. The Canadian industry is more dispersed than here in the UK, but many of the initiatives outlined in this article could be successfully adopted on a Provincial basis. I’m in BC and Alberta in early June so will be following your progress with great interest!

Photo captions:

London rally-1: British pig producers sing a rousing chorus of “Stand by you ham” at the rally in London

Downing Street: Stewart Houston, Chairman of the British Pig Association, (second left) prepares to hand in a petition to the Prime Minister’s residence, 10 Downing Street

Remodelling expands Big Sky sow base

Posted in: Environment, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

Complete remodelling of 600-sow farrow to finish barns into 1800-sow units producing isowean pigs is the route to expanding the sow base at Humboldt, Sask. based Big Sky Farms, which currently has 49,000 sows. And, says production manager Richard Johnson, it will cut overhead costs per sow leading to a lower cost per piglet produced. The company purchased the assets of Community Pork Ventures (CPV) in 2005, a production system that had been based on 600-sow farrow to finish barns, with four units in the 12,000 sow operation holding 1200 sows. However, the Big Sky production model was based on three-site production, with large-scale breeding units, off-site nurseries and contract finishing barns. “As we got to know and work with the CPV system, we thought there was an opportunity to expand and/or retrofit the systems, which in turn would give us a greater return on capital invested,” explains Johnson. “Not only can we spread our central overhead and management costs over more sows but the specialization in just breeding and farrowing leads to better results.”

Complete remodelling of 600-sow farrow to finish barns into 1800-sow units producing isowean pigs is the route to expanding the sow base at Humboldt, Sask. based Big Sky Farms, which currently has 49,000 sows. And, says production manager Richard Johnson, it will cut overhead costs per sow leading to a lower cost per piglet produced. The company purchased the assets of Community Pork Ventures (CPV) in 2005, a production system that had been based on 600-sow farrow to finish barns, with four units in the 12,000 sow operation holding 1200 sows. However, the Big Sky production model was based on three-site production, with large-scale breeding units, off-site nurseries and contract finishing barns. “As we got to know and work with the CPV system, we thought there was an opportunity to expand and/or retrofit the systems, which in turn would give us a greater return on capital invested,” explains Johnson. “Not only can we spread our central overhead and management costs over more sows but the specialization in just breeding and farrowing leads to better results.”

The first unit to undergo the transformation was the company’s Kelsey barn, located near Melfort, Sask. Additional sow pens were made by modifying the existing part slatted finishing rooms, which had pens of 23 pigs. Three pens were made into one, although the pen divisions between the lying areas were left in place. Each pen now holds 30 sows, which are fed on the floor using volumetric drop dispensers. One of the finisher rooms was left with 12 small pens in order to house sick, lame or thin sows, something Johnson knew was essential in a floor-fed system from his previous experience with group housing in the UK. In addition, two of the grower rooms were also converted to sows pens, giving a total capacity for 1120 sows from 30 days into gestation up to removal for farrowing. The remaining 6 grower rooms were used to construct a further 240 farrowing pens, while the original nursery rooms hold piglets ready for shipping. From weaning until 30 days, sows are housed in stalls in the existing breeding and gestation areas.

Experience with the group sow pens has been generally positive, but not without its teething problems, says unit manager Susan Armstrong. “Our biggest problem has been variation in the weight of feed dispensed, which has ranged from 7-12 lb per drop, making it difficult to feed accurately.” Gilts are penned separately and sows are grouped by body condition in order to feed more accurately, something that’s necessary when floor feeding. However, that makes it more difficult to remove sows for farrowing, says Armstrong. “We can’t remove all the sows at one time as we would if they were grouped strictly by breeding date,” she explains. Also, sow behaviour is rather aggressive with floor feeding, although no vulva biting has been noted so far. Scanning sows in the group has proved more difficult than when sows are in stalls. “We carry out the first scan when sows are in stalls in the implantation area, but we also like to do a second confirmation of pregnancy at 65 days,” Armstrong says.

Experience with the group sow pens has been generally positive, but not without its teething problems, says unit manager Susan Armstrong. “Our biggest problem has been variation in the weight of feed dispensed, which has ranged from 7-12 lb per drop, making it difficult to feed accurately.” Gilts are penned separately and sows are grouped by body condition in order to feed more accurately, something that’s necessary when floor feeding. However, that makes it more difficult to remove sows for farrowing, says Armstrong. “We can’t remove all the sows at one time as we would if they were grouped strictly by breeding date,” she explains. Also, sow behaviour is rather aggressive with floor feeding, although no vulva biting has been noted so far. Scanning sows in the group has proved more difficult than when sows are in stalls. “We carry out the first scan when sows are in stalls in the implantation area, but we also like to do a second confirmation of pregnancy at 65 days,” Armstrong says.

Farrowing the target of 85 sows per week started at the beginning of December and the goal is to wean 900 pigs per week at an age of 20-21 days. These are shipped to the USA with another 900 pigs from another barn to make up a full load of 1800. Big Sky has a contract in place for these pigs to be raised in wean-to-finish barns in Iowa, managed by South Central Management Services, but they retain ownership. Finished pigs will be marketed in the US Mid-West but, initially at least, not tied to a specific packer.

While the decision at the time was to finish pigs in the USA, they could just as easily be reared in low-cost contract finishing barns in Saskatchewan, says Richard Johnson. “It’s currently a lot more attractive to finish in the US, but that could change.” The main motivation for the unit remodelling was to improve return on capital, he stresses. “We will make more money doing this than operating a farrow to finish operation. We modelled a range of different scenarios for these barns with a range of feed prices and in every case the farrow to isowean option was the most profitable.”

Big Sky plans to convert more of the ex-CPV units, drawing on the experience of this first one, especially how the group housing works. “It may prove best to remove the partial pen divisions in the group pens, to allow for sows to move around freely while feeding.” Johnson feels. “Also, we may need to fine-tune space allowances and how we group sows according to age and condition.” So far, though, performance has been up to expectations, with the mainly gilt herd farrowing 11.9 born alive per litter.

In time, converting all the ten 600-sow barns would allow an increase in the company’s sow base of 12,000, but Johnson says that’s a long-term goal. “We do want to expand in order to reduce cost,” he says. “Also, having a lot of sows in group housing will give us additional marketing opportunities and could allow us to develop added value pork products.”

Photo captions:

- New_Sow_pens-1.jpg: Richard Johnson discusses the group sow pens with unit manager Susan Armstrong

2. Sows in group pens-1.jpg: Sows lie quietly in the converted finishing pens

Recommendations for procuring DDGS for hog rations

Posted in: Uncategorized by admin on | No Comments

Dried Distillers Grains with Solubles (DDGS), a co-product of the rapidly growing ethanol industry is an increasingly available ingredient that can be used cost effectively in hog diets. However, special attention needs to be given to the quality of the DDGS to be used in pig feeds as there is a large variation in quality between DDGS sources. Receiving low quality DDGS into a feed mill and including it in pig diets can have negative economic consequences on pig performance. Pig producers and pig feed manufacturers must ensure they are procuring consistently high quality corn DDGS at all times to capture the cost savings of using them. The following recommendations should be considered by swine feed manufacturers for the procurement of DDGS:

Know the source plant

The quality of DDGS can vary between and within manufacturing plants due to differences in manufacturing processes, process control, drying technology and ingredient quality control in the production of DDGS.

Quality standards need to be established and verified before price is a consideration. Use an approved-supplier process to select the plants that can provide DDGS that meet the required quality specifications. This includes obtaining nutrient specifications including proximate and amino acids analysis, mycotoxin analysis, and physical samples of the products.

The following specifications are recommended by Gowans Feed Consulting:

| Check list when buying corn DDGS. | ||

| Item | Minimum | Maximum |

| Crude protein, % | 27.0 | – |

| Fat, % | 9.0 | – |

| Phosphorus, % | 0.55 | – |

| Lysine | 2.80% of crude protein | – |

| ADF, % | – | 12.0 |

| NDF, % | – | 40.0 |

| Mycotoxins (ppm) in the finished feed | ||

| Aflatoxin | – | 0.02 |

| Vomitoxin | – | 1.00 |

| Fumonisin | – | 1.00 |

| Zearalone | – | 0.50 |

Specify the source plant and DDGS quality specifications in the purchase contracts

Incorporate the DDGS quality specifications including the analytical methods for nutrients and the name and location of the approved source plant into the purchase contract. Ensure that the supplier can trace the delivered DDGS back to the origin plant. This is especially important when the supplier is bringing multiple sources of DDGS in by rail and trans-loading onto trucks as there is a risk that DDGS from difference origins can be mixed up. Verify the supplier’s product liability insurance coverage.

Inspect the load and retain a sample

Obtain a representative sample of the DDGS before unloading and verify that it matches the original sample. Inspect the colour (a dark colour may indicate overheating and lower digestible lysine), check the odour (a burnt smell also may indicate overheating) and observe the bulk density and particle size. Reject the load if the representative sample does not closely match the original.

Samples of corn DDGS

Source: University of Minnesota http://www.ddgs.umn.edu

Monitor DDGS for mycotoxins and nutrient content

Mycotoxin content present in DDGS is three times the level that may be present in the corn used for the production of ethanol. Test the DDGS periodically for mycotoxin content to confirm that excessive levels are not present. Require routine nutrient information from DDGS suppliers.

For more information on feeding and buying DDGS visit the following organization’s websites:

U.S. Grains Council

University of Minnesota Distillers Grains By-products Web Site