Evaluation of Methods for Controlling and Monitoring Occupational Exposure of Workers in Swine Facilities

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre by admin on August 9, 2011 | No Comments

This study was aimed to assess the effectiveness of canola oil sprinkling, low crude protein diet, high level of cleaning and manure pH manipulation, in reducing ammonia and respirable dust concentrations in swine production rooms. Among the control measures tested, low protein diet reduced ammonia concentrations while canola oil sprinkling tended to result in lower respirable dust levels. Personal monitoring showed higher level of worker exposure compared to area sampling. Ammonia gas monitors yielded higher readings than the standard (NIOSH) method.

Effects of Altering the Omega-6 to Omega-3 Fatty Acid Ratio in Sow Diets on the Immune Responses of their Offspring Post-Weaning

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre by admin on | No Comments

An experiment was conducted to determine the effects of altering the omega-6 (n-6) to omega-3 (n-3) fatty acid (FA) ratio in sow diets on the immune responses of their off spring post-weaning. Piglets were subjected to an immune challenge by injecting lipopolysaccharide (LPS), a component of gram-negative bacteria which triggers an immune response. Weanling pigs produced from sows consuming different n-6:n-3 FA ratios respond differently to an LPS induced immune challenge. This allows us to conclude that the FA profile of a sows diet may affect the response of her offspring to immune challenges which occur regularly at the time of weaning.

Development of Diets for Low Birth-Weight Piglets to Improve Post-Weaning Growth Performance and Optimize Net Returns to the Producer

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre by admin on | No Comments

An experiment which utilized 17 weeks of production was designed to examine the response of weanling pigs to diet complexity. Piglets were divided at weaning (28 days) into heavy or light body weights and fed either a simple diet for 14 days or a complex diet for 1 or 4 days, followed by the simple diet. Feeding the complex diet for 4 days improved growth performance for the first week following weaning when compared to feeding it for 0 or 1 day. Pigs which were lighter at birth, lost less body weight at weaning, and showed a greater positive response to the complex diet than heavier birth-weight pigs. Phase 1 diet could be used more efficiently and cost effectively by targeting it specifically to the lighter pigs at weaning.

Can we feed mycotoxin contaminated feed to pigs?

Posted in: Prairie Swine Centre, Production by admin on July 14, 2011 | No Comments

Deoxynivalenol (DON) is a mycotoxin produced by fungi which may contaminate cereal grains, including barley and wheat. The contamination is especially problematic when wet, warm conditions prevail during the growing season. The ingestion of grain that is severely contaminated by DON will cause overt symptoms such as vomiting (hence the common name “vomitoxin”). Less dramatic, but more frequently observed symptoms, reduced feed intake and growth, will result when pigs consume feed with a lower concentration of the mycotoxin. The Canadian Feed Inspection Agency suggests that 1 ppm mycotoxin in feed is a safe upper limit for swine.

Deoxynivalenol (DON) is a mycotoxin produced by fungi which may contaminate cereal grains, including barley and wheat. The contamination is especially problematic when wet, warm conditions prevail during the growing season. The ingestion of grain that is severely contaminated by DON will cause overt symptoms such as vomiting (hence the common name “vomitoxin”). Less dramatic, but more frequently observed symptoms, reduced feed intake and growth, will result when pigs consume feed with a lower concentration of the mycotoxin. The Canadian Feed Inspection Agency suggests that 1 ppm mycotoxin in feed is a safe upper limit for swine.

There are several feed additives available which reportedly reduce the impact of the mycotoxin on the pig. Modes of action vary, and include; binding the mycotoxin in the gut and preventing absorption, chemically transforming the toxin to decrease its toxicity, or enhancing immune system function.

The overall objective of this experiment was to determine the effect of these feed additives on the performance of nursery pigs fed diets contaminated with DON.

We used 5 nurseries for this experiment, 24 pens per nursery and 4 pigs per pen. Pigs were fed starter diets for 14 days before being offered the treatment diets (BW 9.02 ± 0.36 kg) for the next 14 days. All starter diets contained in-feed antibiotics.

Treatment diets were formulated to meet or exceed all requirements for pigs of this age. A positive control diet contained no contaminated corn, while the negative control diet was formulated with contaminated corn but no feed additives. Samples of corn which were pre-analyzed and shown to contain DON were used for 70% of the corn (35% in the final diet) in diets 2 to 12 to provide 2 ppm DON in the final diet. This concentration was chosen because a preliminary experiment indicated this amount would cause a measurable reduction in feed intake but would not be fatal.

Performance results are shown in Table 1. Pigs on the positive control tended to be heavier than those on the negative control by day 22 (0.50 kg, P = 0.09). Overall, pigs consuming diets contaminated with DON had reduced ADG and ADFI compared to those consuming the positive control diet free of DON (P < 0.001). Weekly measurements of body weight and feed intake showed that the decline in feed intake preceded the decline in growth (data not shown).

Average daily gain and ADFI of pigs on the positive control was superior to those consuming the DON contaminated diet, regardless of the feed additive used. None of the feed additives ameliorated the effects of DON on feed intake or gain. Feed efficiency was unaffected by treatment (P > 0.05).

Based on a literature search and our preliminary experiment which indicated that 2 ppm would elicit a detectable decrease in feed intake but was non-fatal, we formulated the treatment diets to this level. Analyses of the diets indicated a mean concentration in the DON containing diets of 1.99 ppm, however, the individual diet concentrations ranged from 1.57 to 2.61 ppm.

The 1 tonne totes of contaminated corn were initially sampled from about 10 different locations within each tote to a depth of about 1 metre. These samples, composited by tote, were sent to two different labs for analyses for DON and moulds. The results were extremely variable, within and between the labs. Results from lab “A” ranged from 2.4 to 5.5 ppm with a mean of 4.5 while the results from lab “B” were 2.2 to 9.6 ppm and a mean of 6.9. We didn’t use the totes which displayed the most variability, however, the DON concentrations in our diets were still quite variable (Table 1).

The above illustrates the difficulty of working with mycotoxins. Obtaining representative samples for mycotoxin testing is very difficult, however it is imperative that a good sample is obtained or the results will be irrelevant. It has been estimated that almost 90% of the error associated with mycotoxin testing can be attributed to the method used to obtain the original sample. Because contamination within a field may be localized, a truck-load which has come directly from a field at harvest is likely to contain only discrete areas of contamination. Moreover, mycotoxin contaminated grains are heavier, thus within a truckload or during storage, some stratification may occur.

The “Grain Inspection, Packers and Stockyards Administration (GIPSA) of the USDA only recognizes samples which have been obtained using a probe. Moreover, at least 4 samples should be taken from each lot, preferably 7 to 9, depending on the size and thickness of the trailer. A 2000 to 2500 gram sample should be obtained. This sample should be ground and then subsampled to obtain the approximately 100 gram sample required by the lab. Producers are advised to contact the laboratory they will be using for the analyses to obtain specific sampling procedures and amounts required.

In summary, when nursery pigs were fed diets contaminated with approximately 2 ppm DON, feed intake declined by 10 % and growth by 7%. None of the feed additives mitigated this response, however, actual concentrations of DON in the test diets varied. This variability is an illustration of the difficulties inherent in correct sampling and analysis for mycotoxins.

Acknowledgements

Strategic funding was provided by Sask Pork, Alberta Pork, Manitoba Pork Council and Saskatchewan Agriculture and Food Development Fund.

![]() Pork Insight was developed to address producer and industry needs for timely and accurate information related to pork production and is designed to help you find the information to help you fine -tune your operation. The Pork Insight database can be found online at www.prairieswine.com

Pork Insight was developed to address producer and industry needs for timely and accurate information related to pork production and is designed to help you find the information to help you fine -tune your operation. The Pork Insight database can be found online at www.prairieswine.com

Table 1: Analyzed concentrations of DON in treatment diets and effect on performance of nursery pigs (initial BW 9.02 kg).

|

Trt # |

Treatment |

DON ppm |

|

BW Day 22a |

ADG, kg/d |

ADFI, kg/d |

Gain:Feed |

|

1. |

Positive controlb |

Negc |

|

21.72 |

0.58 |

0.88 |

0.67 |

|

2. |

Negative controld |

1.57 |

|

21.10 |

0.55 |

0.80 |

0.69 |

|

3. |

Trt 2 + Ing. A |

1.33 |

|

20.83e |

0.54e |

0.75e |

0.72 |

|

4. |

Trt 2 + Ing. B |

1.75 |

|

21.27 |

0.56 |

0.80e |

0.71 |

|

5. |

Trt 2 + Ing. C |

1.95 |

|

20.74e |

0.53e |

0.80e |

0.68 |

|

6. |

Trt 2 + Ing. D |

1.76 |

|

20.75e |

0.53e |

0.79e |

0.69 |

|

7. |

Trt 2 + Ing. E |

1.81 |

|

20.74e |

0.53e |

0.78e |

0.69 |

|

8. |

Trt 2 + Ing. F |

1.87 |

|

21.06 |

0.55 |

0.80 |

0.69 |

|

9. |

Trt 2 + Ing. G |

2.09 |

|

21.03 |

0.55e |

0.79e |

0.69 |

|

10. |

Trt 2 + Ing. H |

2.56 |

|

20.46e |

0.52e |

0.74e |

0.71 |

|

11. |

Trt 2 + Ing. F + G |

2.61 |

|

20.46e |

0.52e |

0.76e |

0.69 |

|

12. |

Trt 2 + Ing. E + B |

2.57 |

|

20.33e,f |

0.52e |

0.75e |

0.69 |

|

Statistics |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

SEM |

|

|

0.25 |

0.01 |

0.03 |

0.02 |

|

|

Overall P value |

|

|

0.009 |

0.009 |

0.11 |

0.81 |

|

|

P value |

|

0.09 |

0.08 |

0.06 |

0.36 |

|

|

|

P value (Contrast) |

|

0.0004 |

0.0003 |

0.0008 |

0.13 |

|

|

|

P value (Contrast) |

|

0.20 |

0.20 |

0.35 |

0.77 |

|

aDay 22 of the experiment, day 36 post-weaning.

bUsed exclusively non-contaminated corn.

cNegligible

dFormulated to contain 2 ppm DON

eDifferent from Trt 1, (positive control; P < 0.05).

fDifferent from Trt 2, (negative control; P < 0.05).

Industry Crisis – Census confirms producer devastation

Posted in: Economics, Prairie Swine Centre by admin on | No Comments

The April census data showed the extent of the devastation being wreaked in the Canadian pork industry, with almost one-fifth fewer (19.3%) producers than in the same month of 2007. Total pig numbers for the country were down 11.7%, indicating that the exodus was mainly among the smaller producers. Atlantic Canada showed the biggest drop in total pig numbers, with a massive 25.5% drop and Alberta and Saskatchewan both showed a 16.8% reduction. Other than British Columbia’s fall of 6.9%, the lowest drop in numbers was in Quebec, where the ASRA program helps to maintain hog prices.

Table 1: Percentage change in pig numbers – April 2007 to April 2008

CAN AB SK MB

Total pigs -11.7 -16.8 -10.3 -2.0

Breeding stock -4.6 -7.1 -3.3 -1.4

Other pigs

< 20kg -9.6 -15.4 -7.8 -5.3

>20kg -17.2 -19.1 -22.1 -13.7

In the western provinces breeding pig numbers dropped most in Alberta, at 7.1%, while Manitoba had just a 1.4% reduction in sows, gilts and boars. However, in the East, Ontario fell 7.9% while, as might be expected, Quebec was the lowest with 2.9% fewer breeding animals. The under 20kg category showed substantial reduction in numbers in Alberta, BC and Ontario, with -15.4%, -25.2% and -14.4% respectively, while losses were lower in Manitoba (-5.3%), Saskatchewan (-7.8%) and Quebec (-5.0%). Reflecting the huge trend towards shipping young pigs south of the border, Saskatchewan’s pigs in the over 20kg category fell by 22.1% and Alberta’s by 19.1%, while Manitoba’s numbers fell by 13.7%. During the first 3 months of 2008 an estimated 2.9 million pigs were exported, a 25.9% increase over the same period last year. At the same time, domestic slaughter of hogs slipped 1.1%, although this number is likely to increase sharply as supplies of market hogs dry up.

All eyes will be on the July census figures, which are likely to show further reductions. Although anecdotal evidence suggests that the number of producers making the decision to leave the industry is now far fewer, it will likely be another six months before pig numbers stabilize.

Prairie Swine Centre suspends operations at Elstow unit

Reflecting the current malaise in the pork industry, the Prairie Swine Centre announced on May 9th that its PSC Elstow Research Farm would be suspending operations due to the unprecedented losses in the pork business. The unit, a 600-sow farrow to finish barn, designed to support research work in a commercial-style barn, opened in April 2000. The mandate of the facility is to address the needs of the pork industry for research work using a size and scale typical of the commercial industry. Research to address these needs will continue to be the focal point at the remaining Prairie Swine Centre facilities.

Dr. John Patience, President and CEO of PSC Elstow Research Farm, acknowledges the magnitude of the disappointment and distress this decision has on its employees, as well as on the staff at Prairie Swine Centre, and indeed on the broader Canadian pork industry. “The fact that all pork farms in Canada and virtually every other pork producing nation in the world are being devastated by the current market conditions is little solace to the many people who have worked hard to operate the farm and have come to rely on the knowledge generated from the research conducted there”. “We have long-term confidence in the future of the Canadian pork industry as a favoured supplier to meet the growing demand for the world’s most popular meat protein; however the particular circumstances of this barn make it unviable in the short-term. From the beginning, the strength of this business was its mirroring of real commercial production conditions. In the end, these parameters such as debt structure, the devaluation of the US dollar upon which Canadian pork prices depend, unprecedented increases in grain and protein meal prices and underestimating the impact of research functions on an operating farm has resulted in this business decision to suspend operations until conditions improve.”

In spite of this setback, a new initiative started over two years ago is now complete. The $2 million renovation at the original barns located at Prairie Swine Centre will reduce operating costs, making the farm a more competitive pork producer.

Alberta strategy focuses on added value and better marketing

The final draft report on the Alberta pork industry’s revitalization strategy is now completed and details were presented to the province’s pork producers at two open industry meetings at the end of May.

“This strategy is about leading our industry in a new way,” says Herman Simons, Alberta Pork chairman and Tees, Alta. pork producer. “It’s called ‘The Way Forward’ because our industry is in unprecedented distress and we believe that we need to develop new options if pork producers are to survive this distress and have sustained profitability in the future.”

The strategy was developed by Toma and Bouma Management Consultants and the George Morris Centre, who in turn consulted with appropriate resources both nationally and internationally. The first pillar of this broad analysis, a state-of-the-union report, was completed in March and made available to producers. The report, entitled “The Way Forward, The Situation Assessment of the Alberta Pork Industry,” outlined the situation the industry faces and reviews developments from around the world as a basis for evaluating new options.

“The second pillar report, which is just being released, is the actual strategy for moving ahead with repositioning our product in the marketplace,” says Simons. “The Alberta Pork board has reviewed the draft document, but before we move through final approval, we wanted to give producers an opportunity for direct input. This will be important as we work together with industry stakeholders to implement this strategy.”

The strategy vision, he says, is a highly connected pork industry capable of delivering differentiated, high quality, safe pork products in a sustained manner, with the flexibility to respond to continually changing markets and market conditions. The strategy seeks to move the industry out of the highly competitive and unprofitable production of low-cost bulk pork products. Instead, the industry focus will be on producing high-value pork products in demand by consumers in domestic and global niche markets.

The repositioning strategy basically covers four areas, says Simons. First is to establish system integrity in production, processing and marketing to create a highly connected industry through proactively managed supply chains between the processing sector and producers.

Second is to develop new product marketing capability, the establishment of new business-to-business skill sets that develop long-term supply relationships with a set of targeted markets and customers.

Third is to address cost challenges by developing strategies to reduce the two major cost items facing pork production: feed grains and labour.

Finally, the goal is to create a favourable business environment, ensuring that the industry has the necessary public and private services, tools and instruments to successfully compete in a global meat industry.

“We realize this is not an easy path to the future for pork producers and that there are no simple solutions to our challenges,” says Simons. “However, the report has identified several strengths within our industry and we have confidence in the ability of our producers and processors to work toward capturing those in a realistic fashion.

USDA agrees to help US pork producers

The US National Pork Producers Council (NPPC) commended the Bush administration for its decision to lend assistance to US pork producers to help them weather the current economic crisis in the hog business and announced in May. The US Department of Agriculture (USDA) is purchasing up to US$50 million of pork products, which will be donated to child nutrition and other domestic food assistance programmes.

NPPC representatives had previously met with agriculture secretary Ed Schafer to urge him to take immediate action to address a crisis that over the past seven months has cost the pork industry more than $2.1 billion, says a news release from the producer organization.

Economists have estimated that the industry will need to reduce production by at least 10% – meaning a reduction of 600,000 sows – to restore profitability. Such a cutback, however, could result in less-efficient packing plants closing, less manure for crop fertiliser and correspondingly a need for more man-made, foreign-produced fertiliser, a hike in pork retail prices because of a smaller supply and lost jobs, says the NPPC.

“The action by USDA to buy additional pork will benefit America’s pork producers, the US economy and the people who rely on the government’s various food programs,” said NPPC president Bryan Black. “It will help our industry reduce the herd and thereby bring supply and demand back into balance and allow producers to continue to provide consumers with economical, nutritious pork.”

EU production falls and prices increase

There now seems to be some light at the end of the tunnel for European pig producers following a reduction in herd size in most countries. This has now led to strengthening prices, although industry leaders have pointed out that there is still a long way to go before producers are profitable again. Reports predict that pork production within the EU as a whole will be 4.1% lower in the final quarter of the year compared to 2007.

British pig production, with its high production costs, is still under major pressure and sow culling has been running at the highest level in Europe. In January the number of breeding stock slaughtered rose by 46%; in February, the increase in comparison to 2007 was 40% and March saw a growth of 18%. Having halved in size over the last 10 years, the industry looks set to shrink even more.

Prince Charles waded into the battle British producers are having with supermarkets to get a fair share of the retail price of pork. “My heart goes out to all those farmers who are facing such desperate problems as a result of the huge rise in feed costs,” said Prince Charles in a message to the pig industry. “Thanks to the enormous efforts of BPEX (British Pig Industry Executive) and the National Pig Association, there is a growing awareness of the problem, and those retailers who are raising their prices as a result should be congratulated. However, little, if any, of the increase is being passed down the chain to the farmers and, unless urgent action is taken, this country’s pig sector, which has never received subsidies, could be decimated. This would be a tragedy for this country which produces some of the finest quality pigs and which operates according to the highest standards of husbandry and animal welfare,” said the letter.

Spain, the second largest producer of pigs in the EU, is also feeling the pinch, according to pig industry association Anprogapor, which says its members are struggling with rising feed costs. It estimates that 15 per cent of the 70,000 pig producers in Spain have now ceased production. Production costs are currently around €1.20 per kilo of delivered weight, while market prices half-way through 2007 were reaching around €0.90, says a report.

Anprogapor says the situation is unsustainable and that around 200,000 sows have been taken out of production. The result has brought an increase in market prices, but it is not high enough for more farmers to reach profitable levels.

A four-year long drought is exacerbating the situation and provincial governments continue to press for water supplies to be drafted in from neighbouring countries such as France.

Danish producers have always taken a long-term view of the ups and downs of the hog cycle, but their confidence appears to have been shaken by events over the past year. Urged by their industry leaders to stick it out until prices improve, many have decided enough is enough and quit the business. Total pig numbers were down by 10.4% in April 2008 compared with the same month last year, with a similar drop in the number of sows.

Australian shock at lack of government support

Australia’s pig farmers expressed shock when their hope of import safeguards and extra support for the industry were dashed with the publication of the final report to the Federal Government from the Productivity Commission (PC), which was looking into the effect of cheaper imports on the poor profitability of producers.

Australian Pork Limited (APL) CEO Andrew Spencer said that the industry is imploding due to cheap imports of frozen pig meat. Added to this situation is high grain prices that are making local production completely unviable, he said. “To continue to ignore the fact that all of Australia’s pork imports come from countries that actively subsidise their pig farmers and their pork industry with tax payers funds, laughs in the face of fair trading conditions and a free trade environment.” Mr Spencer said 70 per cent of bacon and ham are sourced from overseas countries. Despite the high levels of on-farm efficiencies gained by Australian pig farmers over the past five years, Mr Spencer said the industry cannot compete in “this distorted, totally unbalanced trading environment”.

Eye on Research – The effect of space and group size on finisher performance

Posted in: Prairie Swine Centre, Production, Uncategorized, Welfare by admin on | No Comments

With the current shift in the industry toward housing pigs in groups of 100 to 1,000 per pen, questions have been raised as to whether pigs can perform as well in large groups as they do in small ones. Recent work at the Prairie Swine Centre examined how housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations affects production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables. The studies looked at the effects of small (18 pigs) vs. large (108 pigs) group sizes provided with 0.52 m2/ pig (crowded) or 0.78 m2/pig (uncrowded) of space on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Eight, 7-8 week-long blocks, each involving 288 pigs, were completed. The average liveweight at the beginning of the study was 37.4kg. Overall, average daily gain (ADG) was 1.032 kg/day and 1.077 kg/day for crowded and uncrowded pigs respectively, which was a highly significant difference. Differences between the space allowance treatments were most evident during the final week of study.

Pigs in the crowded groups spent less time eating over the eight-week study than did pigs in non-crowded groups. However, average daily feed intake (ADFI) did not differ between treatments. Overall, ADG of large-group pigs was 1.035 kg/day, whereas small group pigs gained 1.073 kg/day. Average daily gain differences between the group sizes were most evident during the first two weeks of the study.

The investigation found that, over the entire study, large groups were less efficient than small groups. Although large-group pigs had poorer scores for lameness and leg scores throughout the eight-week period, morbidity levels did not differ between the group sizes. Minimal changes in postural behaviour and feeding patterns were noted in large groups.

An interaction of group size and space allowance for lameness indicated that pigs housed in large groups at restricted space allowances were more susceptible to lameness. Although some behavioural variables, such as lying postures, suggested that pigs in large groups were able to use space more efficiently, overall productivity and health variables indicate that pigs in large and small groups were similarly affected by the crowding imposed in this study.

The trial indicated no difference in the response to crowding by pigs in large and small groups. Little support was found for reducing space allowances for pigs in large groups.

WHJ comment: There is no doubt that the North American pork industry has enthusiastically embraced large group grow-finish systems in order to obtain the benefits of auto-sorting equipment, which leads to more optimal market weights and saves labour. However, little is known about the implications for pig performance and welfare. This study suggests that space allowance has a bigger effect on growth than group size, although ADG was better for the small groups. The suggestion that pigs in large groups make better use of space and therefore need less space per pig seems to be disproved by this work. Even though there are disadvantages in both performance and some measures of welfare, the trend towards large groups is likely to continue due to the magnitude of the benefits.

Reference: B. R. Street and H. W. Gonyou. – Effects of housing finishing pigs in two group sizes and at two floor space allocations on production, health, behaviour, and physiological variables.

J. Anim Sci. 2008. 86:982-991. doi:10.2527/jas.2007-0449

Survival strategies – When every penny counts

Posted in: Economics, Prairie Swine Centre, Production by admin on | No Comments

Introduction

It is a significant challenge to suggest how a Canadian pork producer in today’s economic environment can turn a loss into a profit. Indeed the “perfect storm” of pork prices, exchange rate and input costs have made losses of $30-$50/hog the norm over the last several months. It is the intent of this paper to reinforce production practices, backed by research and actual commercial practice, that can produce savings of not just $2-3 per market animal but multiples of that. Too often do we hear “I am doing everything possible already” in reference to cutting costs. Production systems are living entities with fluctuations in productivity, management and staff that are overwhelmed with daily distractions and in-barn procedures which evolve whether you want them to or not. There are opportunities, and every dollar saved is one less dollar borrowed under the present conditions. The following is a checklist to take to the barn and help you evaluate where the opportunities exist in your operation.

It is a significant challenge to suggest how a Canadian pork producer in today’s economic environment can turn a loss into a profit. Indeed the “perfect storm” of pork prices, exchange rate and input costs have made losses of $30-$50/hog the norm over the last several months. It is the intent of this paper to reinforce production practices, backed by research and actual commercial practice, that can produce savings of not just $2-3 per market animal but multiples of that. Too often do we hear “I am doing everything possible already” in reference to cutting costs. Production systems are living entities with fluctuations in productivity, management and staff that are overwhelmed with daily distractions and in-barn procedures which evolve whether you want them to or not. There are opportunities, and every dollar saved is one less dollar borrowed under the present conditions. The following is a checklist to take to the barn and help you evaluate where the opportunities exist in your operation.

The focus is on the cost areas with the greatest potential for payback for the efforts invested. These are in order of importance and relative size of annual expenditure: feed (52.7%), wages & benefits 11.2%, and utilities & fuel 4.7%. These three account for nearly 70% of all expenditures on a typical farm in western Canada in 2007, so our approach to addressing costs will be confined to these areas.

Feeding Program

This begins with defining the objective of the feeding program that can be any one of the six objectives in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Objectives of a feeding program

1. Maximize return over feed cost/pig sold

2. Maximize return over feed cost/year

3. Maximize expression of genetic potential

4. Achieve specific carcass characteristics

5. Achieve specific pork characteristics

- Minimize operational losses

Action #1: Feeding program objectives must be clearly defined;

Objectives can and indeed will change over time |

The purpose of defining the program makes it possible for the nutritionist to assist in diet formulation and ingredient selection to achieve that end. So the first opportunity for cost reduction is – Are we formulating to minimize operational losses? This includes a review of selecting optimum energy levels, defining lysine:energy ratios, defining the ratio of other amino acid levels to lysine, setting mineral levels (even withdrawing in late stage finisher diets) and making use of opportunity ingredients. The outcome should be a feed budget similar to Figure 2. The regular matching of actual feed usage by diet type to the budget is the exercise in Figure 3 which shows that after a 5 month period in fact this 600 sow farrow-to-finish farm had excessive use of some of the most expensive diets on the farm and resulted in an average cost increase of almost $6 per market hog. But the owner thought they were doing “everything they could” because they had a competitive feed budget. The problem was not the budget but the fact it was not being adhered to for any number of reasons, perhaps as simple as not explaining to the person making or delivering the feed that the number of pigs in the nursery was below budget, in this case because of a PCVAD outbreak.

Figure 2: Example of a typical western Canadian feed budget

Diet Pig Wt., Days A.D.G., A.D.F.I., Feed,

kg g/d g/d kg/pig kg.pig kg/pig

St #1 6 4 115 125 0.5

St #2 7 to 8 6 300 330 2.0

St #3 8 to 14 13 475 620 8

St #4 14 to 22 13 600 870 11

St #5 22 to 35 17 765 1,224 21

Gr #1 35 to 50 16 865 1,900 31

Gr #2 50 to 65 16 920 2,300 38

Fi #1 65 to 80 16 930 2,600 46

Fi #2 80 to 95 16 930 2,850 46

Fi #3 95 to 105 11 880 3,000 38

Fi #4 105 to Mkt 12 830 3,000 32

Figure 3: Reconciliation of actual feed usage versus budget

Diet Budget Actual (5 month avg)

Wean diet 2.5 3.3*

Starter 1 8 9.1*

Starter 2 11 12.8*

Starter 3 21 23.4*

Grower 1 31 40.1*

Grower 2 38 43.3*

Barrow fin1 46 41.6

Barrow fin2 46 42.9

Barrow fin3 38 43.1*

Barrow fin-mkt 32 46.5*

Gilt fin1 46 48.0

Gilt fin2 46 46.6

Gilt fin3 36 46.1*

Gilt fin-mkt 30 47.4*

Gestation 37 18.1

Lactation 22 18.3

Cost/pig marketed $83.42 $89.35

Difference $5.93

Numbers in RED* are greater than 10% over budget

Other aspects of the feeding program that need to be evaluated include evaluating the energy content of the final diets and implementing the Net Energy system to seek further savings by crediting the most accurate energy value available to each ingredient. Reformulating frequently is important when commodity prices move up or down. The general “rule of thumb” is to reformulate whenever the main grain and protein ingredients move by a pre-determined amount (for example $5-10 per metric tonne).

Alternative feed ingredients at times can be the single largest opportunity to reduce feed costs. This includes co-products of the ethanol, bakery and food processing industry but also includes common ingredients like corn. Currently in western Canadian diets implementing a change from wheat to corn could save as much as $4-5/pig marketed depending on your local cost of wheat.

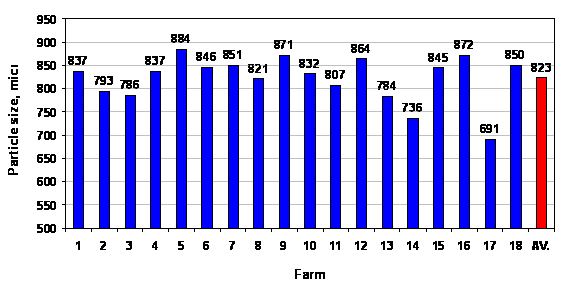

Once the diet has been formulated there are still opportunities to reduce costs by observing particle size stays within the 650-700 micron range to ensure optimum digestibility. Frequently, due to screen wear, improper screen size or hammer wear, the feeds milled on farm are significantly over the 700-micron threshold (surveys show a range of particle size 700-900 microns – Figure 4). For every 100 microns under 700 the feed conversion improves 1.2%. With feed costs today of $80 per finished hog, moving from say a 3.0 F/G to a 2.96 F/G (the effect of 1.2% improvement, or 100 micron reduction in feed particle size) is worth $1.00 per pig marketed.

Figure 4: On-farm survey of average feed grain particle size

| Target of 650 um |

From: Stirdon Betker, Alberta

Please view our Survival Strategies publications on our website www.prairieswine.ca for more tips like:

- Moving from 2 phases to 4 phase feeding programs can easily save $1-2/pig

- Trace minerals and vitamins can be removed from last three weeks of finishing diet (not for gilts for breeding or pigs on Paylean)

- Use of phytase and reduction of dicalcium phosphate in diet has saved $0.50 per pig or more under some market conditions

Labour

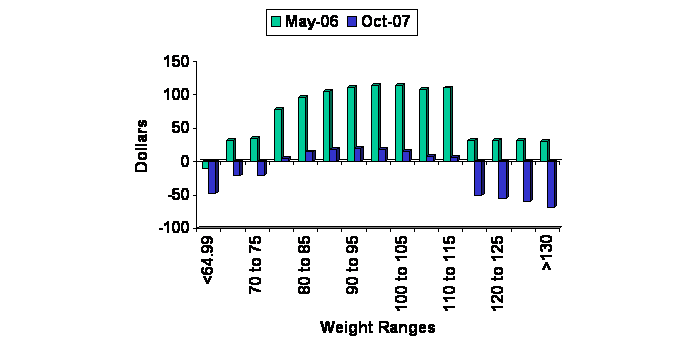

Which is more important – breeding sows or shipping pigs? Although the question is not really which is more important, it does point to the two areas where our people have a significant impact in our success as a production unit. Figure 5 shows one farm’s analysis of how management and labour have to respond when market conditions change. The most profitable hog in May 2006 provided a carcass of 100-105 kg whereas that same farm maximized returns by dropping carcass weights 5kg in October 2007 in response to declining hog prices and increasing feed prices. Once the new target is established, consistently hitting the target is important. Unfortunately many packers still report that only 66% of the hogs they receive fall into “core”. This is unfortunate since weighing, marking and forecasting growth rates should allow the personnel to hit 85% in core consistently. The loss due to this slippage is approaching $2.00 per hog marketed.

Figure 5: On farms analysis of carcass weight relative to returns at two time periods

Action #8: In May, 2006, return over feed cost was maximized in carcasses weighing 100 to 105 kg; in October, 2007, returns were maximized in carcasses weighing 95 to 100kg

Utilities

Utilities are the third largest expense in pork production after feed and labour. This cost area has seen significant increases across Canada over the past 5 years. In 2003 we did extensive analysis on the effect of ventilation rate and set point temperature adjustments that can save on energy costs. At the time we found losses of $1 per pig marketed were likely when a finishing barn was over-ventilated by just 10% in the winter. Today electricity prices are three times what we paid in 2003. Our opportunity for savings of up to $3 per hog marketed is possible by ensuring our ventilation systems are performing properly.

An extensive analysis of utility costs is being undertaken in a variety of barns across Saskatchewan. The initial results reported in Figure 6 show that the range of energy use is four fold across various farrow-to-finish operations. Although disappointing for those farms at the high end, it does indicate that there is significant opportunity to reduce costs incurred for utilities – at least $3-5 per pig marketed. Some of the differences contributing to these vast differences in cost include:

- Limit use of heat lamps in farrowing and move to heat mats

- Move from incandescent to T-8 fluorescent bulbs

- Reduce the number of hours of light or amount of light in nursery and grow finish rooms

- When fans need replacing select new ones on the basis of energy efficiency

Figure 6: Survey showing range in energy use across farm types

– Energy, $/100kg pig, over 3 years

Barn type No. of barns Mean Min Max

Farrow-finish 8 6.76 3.31 12.24

Nursery 2 1.70 1.36 2.48

Finish 4 1.35 0.95 2.07

Farrow 2 13.08 11.83 13.93

Farrow-nursery 2 16.21 8.93 23.06

Nursery-finish 1 2.66 1.71 4.06

Additional information will be forthcoming in this area as research uncovers the hidden profit robbers hiding in our utility bills.

Most farms don’t receive a water bill but waste here also contributes to farm costs. Scientific and industry surveys both point to the fact that about 40% of the water delivered to the nipple is wasted. This wasted water ends up as slurry and increases our manure hauling costs by at least $0.70 per pig. The things to look for:

- In a recent survey 20-70% of nipples provided flow rates in excess of recommendations. This excess water is beyond the pig’s capacity to consume it resulting in higher waste.

- Water disappearance is 34% less on wet/dry feeders compared to dry feeders and wall mount nipples.

- Nipples installed at 90o to the wall should be located at shoulder height; nipples located 45o to the wall should be 2 inches above shoulder height (a well-positioned nipple will reduce water wastage to 25% of total volume delivered).

- Replacing nipple drinkers with swing drinkers, bite-ball nipples or bowls has also been shown to decrease wastage.

Productivity

When prices are low and losses are high it is easy to turn our attention away from the demanding management of sow reproduction, “so what if we wean a few less pigs, they are not worth anything any way”. However each pig contributes to carrying the overhead of all those fixed costs our barns incur. Actually, outside of feed and trucking, most costs are fixed in our systems so the impact of sow productivity can be profound. For example, in November we completed an analysis asking what if we move from 22 pigs weaned (20.7 pigs sold) per year to 28 pigs weaned (26.3 pigs sold) per year? During this November period our breakeven price for producing a market hog dropped from $1.60/kg to $1.47/kg when looking at just the impact of sow productivity.

Conclusions

There are opportunities for savings on every farm in Canada. Finding these savings takes a methodical and careful process of comparing our targets to what we are actually achieving – doing this on a regular basis will frequently find opportunities to save. Perhaps savings of $15/hog are possible. These savings don’t all exist on all farms but some of them exist on some farms and it is our job to find them and correct them. Then next month look again and find those that escaped our gaze the first time, and be committed to doing it over and over again as we work to maintain margins in a challenging commodity market.

Pork Insight was developed to address producer and industry needs for timely and accurate information related to pork production and is designed to help you find the information to help you fine -tune your operation. The Pork Insight database can be found online at www.prairieswine.com

Survival Checklist

| Action # 1: Feeding program objectives must be clearly defined; objectives can and indeed will change over timeAction # 2: Selecting the correct dietary energy concentration can lower costs by $1 – $13 per pigAction # 3: Adoption of Net Energy system for diet formulation can reduce feed costs by $1 and $5 per pig.

Action # 4: Aggressive adoption of a variety of ingredients can reduce feed costs by up to $5 per pig Action # 5: Regular re-formulation of diets can reduce feed costs by $3 to $4 per pig. Action # 6: Tracking implementation of feed budget can reduce costs by $5 per pig. Action # 7: Cost of particle size deviation from target can exceed $1 per pig. Action # 8: In May 2006, return over feed cost was maximized in carcasses weighing 100-105 kg, in October 2007, that same farm found returns maximized in carcasses weighing 95-100 kg. Action # 9: Achieving 85% in core, rather than 66% in core would increase return over feed costs by up to $1.80 per pig Action # 10: Increased sow productivity (from 22-28 p/s/y) can reduce breakeven $13/ckg or about 10%. Action # 11: Operating procedures and equipment can both contribute to excess power consumption. Turn lights off, switch to heat mats and reduce heat lamp use. Action # 12: Improper minimum ventilation (10% above requirement) adds up to $3 per pig Action # 13: On average 40% of water delivered to the nipple is wasted, that is an additional $070/pig in slurry hauling costs. |

News and Views – Dr. John Patience honoured in Alberta

Posted in: Prairie Swine Centre by admin on | No Comments

For the second time in six months, President and CEO of the Prairie Swine Centre, Dr. John Patience, received a Lifetime Achievement Award; this time at the Alberta Pork Congress held March 12-13. The Saskatchewan Pork Development Board presented Patience with a similar award last November. He is leaving his position in June, after 20 years at the centre.

For the second time in six months, President and CEO of the Prairie Swine Centre, Dr. John Patience, received a Lifetime Achievement Award; this time at the Alberta Pork Congress held March 12-13. The Saskatchewan Pork Development Board presented Patience with a similar award last November. He is leaving his position in June, after 20 years at the centre.

Dr. Patience is a graduate of the University of Guelph, where he received a B.Sc. (Agr) in 1974 and a M.Sc. in animal nutrition in 1976. After leaving the University, he began his career in Saskatchewan as a provincial swine specialist. Three years later he moved to Saskatoon where he worked for Federated Co-op as the company’s swine nutritionist and then head nutritionist. He held that position for four years before deciding to return to school. He received a Ph.D. in nutritional biochemistry from Cornell University in 1985.

Dr Patience was instrumental in gaining international recognition for the Prairie Swine Centre for its practical research and communication of information to the industry. Under his leadership the centre has grown and now has a staff of over 50. He is a well-known speaker and has addressed conferences in many parts of the world.

Also presented at the Pork Congress banquet was the Elanco Pork Industry Leadership Award, which went to Jurgen Preugschas of Mayerthorpe, Alberta, a former chairman of Alberta Pork and currently First Vice-President of the Canadian Pork Council.

Photo: John Patience

Weaning at 28 Days. Is Creep Feeding Beneficial?

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre, Production by admin on July 12, 2011 | No Comments

Providing feed to the piglets in the farrowing room, or creep feeding, is practised to ensure a smooth transition onto solid feed at weaning. It is assumed that even a limited intake of the creep feed will familiarize the piglet with solid feed and mitigate a post-weaning growth lag by 1) increasing the body weight of piglets at weaning, 2) encouraging consumption of solid feed immediately post-weaning and 3) initiating the adaptation of the gastro-intestinal tract to solid feed. It was found that by allowing piglets access to a Phase 1 diet in the farrowing room (creep feeding) for the final 7 days prior to weaning on day 28 did not provide a sustained growth benefit, regardless of weaning weight.

For the full text PDF Click Here!

Does Palatability Affect the Intake of Peas in Pigs?

Posted in: Pork Insight Articles, Prairie Swine Centre by admin on | No Comments

The primary use for field peas is as animal feed, particularly swine diets, where they are an economical source of energy and protein. The palatability of peas is a signifi cant concern because it limits the use of this valuable ingredient. In this project, we studied the palatability of peas in swine diets. Our results show that peas used did not cause aversion in pigs, even when inclusion rates were as high as 60%. Pea diets did not cause a taste or post-ingestive aversion, and resulted in consumption levels equivalent to those for soybean meal diets.

For full article PDF click here